FolkWorld #44 03/2011

© Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Music of Greece

More recently, the Hellenic Republic has borne the brunt of recession and financial crisis.

In contrast to the country's impoverishment there is a wealth of Greek folk music...

The music of Greece is as diverse and celebrated as its history. Traditional Greek music pertains many similarities with Middle Eastern music, especially the music of Cyprus, with their modern popular music scenes remaining well-integrated. Music exists as a significant aspect of Hellenic culture, both within Greece and in the diaspora. Greek music is frequently played at parties and festivals, with children and adults both partaking in traditional Greek dancing.

Greek music history

Greece (Hellenic Republic - Ελληνική Δημοκρατία)

Capital:

Greece (Hellenic Republic - Ελληνική Δημοκρατία)

Capital: Athens

Population: 11,3 mio.

Location: Southeastern Europe on the southern end of the Balkan Peninsula,

bordering Albania, the Republic of Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to the east.

Greece is featuring about 1,400 islands, including Cretes.

Greek music history extends far back into Ancient Greece, since music was a major part of ancient Greek theater. Later influences from the Roman Empire, Eastern Europe and the Byzantine Empire changed the form and style of Greek music. In the 19th century, opera composers, like Nikolaos Mantzaros (1795–1872), Spyridon Xyndas (1812–1896) and Spyridon Samaras (1861–1917) and symphonists, like Dimitris Lialios and Dionysios Rodotheatos revitalized Greek art music. However, the diverse history of art music in Greece, which extends from the Cretan Renaissance and reaches modern times, exceeds the aims of the present article, which is, in general, limited to the presentation of the musical forms that have become synonymous to 'Greek music' during the last few decades; that is, the 'Greek song' or the 'song in Greek verse'.

Ancient Greece

In ancient Greece, mixed-gender choruses performed for entertainment, celebration and spiritual reasons. Instruments included the double-reed aulos and the plucked string instrument, the lyre, especially the special kind called a kithara.

Music was an important part of education in ancient Greece, and boys were taught music starting at age six. Greek musical literacy created a flowering of development; Greek music theory included the Greek musical modes, eventually became the basis for Western religious music and classical music.

Byzantium

The tradition of eastern liturgical chant, encompassing the Greek-speaking world, developed in the Byzantine Empire from the establishment of its capital, Constantinople, in 330 until its fall in 1453. It is undeniably of composite origin, drawing on the artistic and technical productions of the classical Greek age, on Jewish music, and inspired by the monophonic vocal music that evolved in the early (Greek) Christian cities of Alexandria, Antioch and Ephesus (see also Early Christian music). In his lexicographical discussion of instruments, the Persian geographer Ibn Khurradadhbih (d. 911) cited the lūrā (bowed lyra) as a typical instrument of the Byzantines along with the urghun (organ), shilyani (probably a type of harp or lyre), and the salandj (probably a bagpipe).

Greece during the Ottoman Empire

By the beginning of the 20th century, music-cafés (καφέ-σαντάν) were popular in Constantinople and Smyrna. There, small groups of musicians from Greek, Jewish, Armenian, and Roma backgrounds would sing and play improvised music. The bands were typically led by a female vocalist, and included a violin and a sandoúri. The improvised songs typically exclaimed amán amán, which led to the name amanédhes or café-aman (καφέ-αμάν). Musicians of this period included Marika Papagika, Agapios Tomboulis, Rosa Eskenazi, Rita Abatzi, Georgia Mitaki (Μητάκη, not Μυτάκη), Marika Frantzeskopoulou, Marika Kanaropoulou. This period also brought in the Rebetiko movement, which featured in İzmir, and had local Smyrnaic, Byzantine, and Ottoman influences.

Folk music

Greek folk traditions are said to derive from the music played by ancient Greeks. There are said to be two musical movements in Greek folk music (παραδοσιακή μουσική): Acritic songs and Klephtic songs. Akritic music comes from the 9th century akrites, or border guards of the Byzantine Empire. Following the end of the Byzantine period, klephtic music arose before the Greek Revolution, developed among the kleftes, warriors who fought against the Ottoman Empire. Klephtic music is monophonic and uses no harmonic accompaniment.

Paleá dhimotiká (Παλαιά δημοτικά "old traditional songs", mainly from Peloponnese and Thessaly) are accompanied by clarinets, guitars, tambourines and violins, and include dance music forms like syrtó, kalamatianó, tsámiko and hasaposérviko, as well as vocal music like kléftiko. Many of the earliest recordings were done by Arvanites like Yiorgia Mittaki and Yiorgios Papasidheris. Instrumentalists include clarinet virtuosos like Petroloukas Halkias, Yiorgos Yevyelis and Yiannis Vassilopoulos, as well as oud and fiddle players like Nikos Saragoudas and Yiorgos Koros.

Aegean Islands

The Aegean islands of Greece are known for nisiótika songs; characteristics vary widely. Although the basis of the sound is characteristically secular-Byzantine, the relative isolation of the islands allowed the separate development of island-specific musics. Most of the Nisiótika songs are accompanied by lira, clarinet, guitar and violin. Modern stars include Effi Sarri and the Konitopoulos clan; Mariza Koch is credited with reviving the field in the 1970s. Folk dances include the chiotikos, stavrotos, ballos syrtos, trata and ikariotikos.

One of the most famous singers of cycladic music is Domna Samiou.

Cretan Music

Crete is an island which is a part of Greece. The lýra is the dominant folk instrument on the island; it is a three-stringed bowed instrument similar to the Byzantine Lyra. It is often accompanied by the Cretian lute (laoúto), which is similar to both an oud and a mandolin. Nikos Xylouris, Antonis Xylouris (or Psarantonis), Thanassis Skordalos, Kostas Moundakis, and Vasilis Skoulas are among the most renowned players of the lýra.

The "tabachaniotika" ([tabaxaˈɲotika]; sing.: tabachaniotiko - Greek: ταμπαχανιώτικο) songs are a Cretan urban musical repertory which belongs to the wide family of musics, like the rebetiko and music of the Café-aman, that merge Greek and Eastern music elements. This genre represents an outcome of the Cretan-Minor Asia's Greek cultural syncretism in East Mediterranean Sea. It developed mainly after the immigration of Smyrna's refugees in 1922, as did the more widespread rebetiko.

Various conjectures are advanced to explain the meaning and origin of the term tabachaniotika. Kostas Papadakis believes that it comes from tabakaniotikes (*ταμπακανιώτικες), which may mean places where hashish (Greek: ταμπάκο 'tobacco') is smoked while music is performed, as was the case with the tekédes (τεκέδες; pl. of tekés) of Piraeus. But a quarter named Tabahana (Ταμπάχανα) existed in Smyrna—a name which has the Turkish root tabak: tanner; tabakhane: tannery. In Chaniá too, there was a quarter with the same name, where refugees from Smyrna lived after the 1922 diaspora. Tabachaniotiko was also the name of a song of the amanés genre, which was popular in Smyrna in the period before 1922, together with some other songs called Minóre, Bournovalió, Galatá, and Tzivaéri. Compare the performance of Greek-Turkish ballos by a Greek ensemble in New York City in 1928, included in the online article on Mediterranean music in America by Karl Signell.

This detail might be critical for the history of Cretan tabachaniotika, since Cretans frequently had contacts with the people and music of Smyrna during the nineteenth century. Cretan musicians believe that the further development of Cretan tabachaniotika took place mainly after 1922, as a consequence of the refugees' resettlement. The genre was popular until the 1950s.

Major features of the tabachaniotika songs are the following:

- Dromoi (sing.: dromos - δρόμος), modal types designated by Turkish names, like rasti, houzam, hijaz, ousak, niaventi, and sabak.

- Instrumental introduction before the song (taximi, pl.:, taximia), where the player explores the dromos.

- Tsiftetéli rhythm, as in the Turkish "belly dance" music example heard in Signell's article.

- Musical instruments like bouzouki, boulgarí (μπουλγκαρί, the Cretan version of the Turkish bağlama, similar to the earliest forms of the bouzouki), and baglamás.

The rebetiko and tabachaniotika often share the political verse, that is, fifteen syllable lines divided into two hemistichs - ημιστίχια (8+7), generally realized as couplets. In Crete such couplets are called mandinádes (μαντινάδες), as are extemporary texts sung to the music of dances, mainly the syrtós, and the kondyliés (οι κοντυλιές).

They focus mainly on the themes of existential grief and lost love, also common to the rebetiko. Songs making fun of Turks, narrative songs, and other songs in dialogue form also belong to this repertory.

Unlike rebetiko (which is described below), the tabachaniotika did not considered underground music and was only sung, not danced, according to Nikolaos Sarimanolis, the last living performer of this repertory in Chaniá. Only a few musicians played the tabachaniotika, the most famous being the boulgarí (a mandolin like instrument) player Stelios "Phoustalieris" Foustalierakis (1911–1992) from Réthymnon. Stelios Foustalieris bought his first boulgarí in 1924. In 1979, he said that in Rethymnon, the boulgarí had been widespread during the 1920s; in every tavern one could find a boulgarí, and people played and sang lovesongs. He said the boulgarí was then the main accompanying instrument of the lyra, together with the mandola. The laouto began spreading in Rethymnon not before the 1930s. Foustalieris played for years as accompanist to the lyrist Antonis Kareklás (in feasts and weddings) and performed any kind of repertory (syrtós, pentozália, pidihtá (lit.: 'jumping up songs'), kastriná, taxímia, kathistiká (lit.: 'sitting-down songs', i.e. music for listening, not for dancing), and even rebetiko). Later, he began playing the boulgarí, as a melodic instrument, with the accompaniment of guitar or mandolin. He also played in a group with musicians (refugees from Asia Minor), who played the outi and sandouri. Foustalieris composed also many songs and recorded them in Rethymnon. In the period 1933–1937 he lived in Piraeus and played together with famous rebetes, like Markos Vamvarakis. He may be considered a musician who merged the musics of Crete, Asia Minor, and Piraeus.

Notwithstanding the dearth of performers, tabachaniotika songs were widespread and could also be performed at domestic gatherings. Notable artists of this genre who were originally refugees from Asia Minor include the bouzouki player Nikolaos "Nikolis" Sarimanolis (Νικολής Σαριμανώλης; born in Nea Ephesos in 1919) as a member of a folk-group founded by Kostas Papadakis in Chaniá in 1945, Antonis Katinaris (also based in Chaniá), and the Rethymnon-based Mihalis Arabatzoglou and Nikos Gialidis.

The Cretan music theme Zorba's dance by Mikis Theodorakis (incorporating elements from the hasapiko dance) which appears in the Hollywood 1964 movie Zorba the Greek remains the most well-known Greek song abroad.

The Cretan musical tradition in its pure form is followed today by several contemporary artists such as the Chainides, Loudovikos ton Anogion, and Yiannis Charoulis. Occasionally, it reaches mainstream popularity through the work of artists such as Etsi De and Manos Pyrovolakis who mix its original form with popular music.

Cyclades

In the Aegean Cyclades, the violin is more popular than the lira, and has produced several respected musicians, including Nikos Ikonomidhes, Nikos Hatzopoulos and Stathis Koukoularis.

Cyprus

Cyprus is an independent country, currently contested between the Republic of Cyprus and the internationally unrecognized Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. Cyprus' folk traditions include dances like the sousta, syrtos, zeimbekikos, dachas, and the kartsilamdhes.

Epirus

In Epirus, folk songs are pentatonic and polyphonic,sung by both male and female singers. Distinctive songs include mirolóyia (mournful tunes) vocals with skáros accompaniment and tis távlas (drinking songs). The clarinet is the most prominent folk instrument in Epirus, used to accompany dances, mostly slow and heavy, like the menousis, fisouni, podhia, sta dio, sta tria, zagorisios, kentimeni, koftos, yiatros and tsamikos.

Ionian Islands

The Ionian Islands were never under Turkish control, and their kantádhes (traditional songs) are based on the popular Italian style of the early 19th century. Kantádhes are performed by three male singers accompanied by mandolin or guitar. These romantic songs developed mainly in Kefallonia in the early 19th century but spread throughout Greece after the liberation of Greece. An Athenian form of kantádhes arose, accompanied by violin, clarinet and laouto. However the style is accepted as uniquely Ionian. The island of Zakynthos has a diverse musical history with influences from Venice, Crete and elsewhere. The island's music heritage is celebrated by the Zakynthos School of Music, established in 1815. Folk dances include the tsirigotikos, ballos, ai yiogis, kerkyraikos and kato sto yialo.

Pontus

The prime instruments in Pontian musical are the kemenche or lyra which bears resemblance to its Cretan, Cypriot and Thracian counterparts. Also the davul, a type of drum, the zurna which varied from region to region with the one from Bafra sounding differently due to its bigger size, the Violi which was very popular in the Bafra region, the Kemane, an instrument closely related to the one of Kappadokia and highly popular in the Kerasounta and Kars regions. Finally worth mentioning are the Defi and Outi.

Thrace

Instruments used in ancient Thracian music such as Bagpipes (gaida) and lyra are still the ordinary instruments of folk music in Thrace. Folk dances include the tripati, sfarlis, souflioutouda, zonaradikos, kastrinos, syngathistos, baintouska and apadiasteite sto xoro. In Thrace, there is also a Muslim, mainly Turkish and Gypsy, minority. The dominant music of Turkey, Halay, had been banned in Turkey because of its Middle East origins in the past. Thus the traditional music of the minority in Greece is usually seen as more genuine Turkish (Halay) than the folk music found in Turkey itself. Halay is a famous dance in the Middle East. It is a symbol for the tempestuous way of life in its place of origin, Anatolia. It is a national dance in Armenia and Turkey. The traditional form of the Halay dance is played on the Zurna, supported by a Davul. The dancers form a circle or line, while holding each other with the little finger. From Anatolia the Halay has spread to many other Regions, like Armenia or the Balkans.

Popular music

Being largely unaffected by the developments of the European Renaissance due to the Ottoman rule (which lasted nearly four centuries), the first liberated Greeks were anxious to catch up with the rest of Europe. It was through the Ionian Islands (which were under the Italian rule and influence) that all the major advances of the European music were introduced to mainland Greeks. The songs of the Islands known as Heptanesian kantádhes (καντάδες 'serenades'; sing.: καντάδα) are based on the popular Italian music of the early 19th century. Kantádhes became the forerunners of the Greek modern song, influencing its development to a considerable degree. For the first part of the next century, several Greek composers continued to borrow elements from the Heptanesian style.

Early popular songs

The most successful songs during the period 1870–1930 were the so-called Athenian serenades (Αθηναϊκές καντάδες), and the songs performed on stage (επιθεωρησιακά τραγούδια 'theatrical revue songs') in revues and operettas that were dominating Athens' theatre scene. Despite the fact that the Athenian songs were not autonomous artistic creations (in contrast with the serenades) and despite their original connection with mainly dramatic forms of Art, they eventually became hits as independent songs. Italian opera had a great influence on the musical aesthetics of the Modern Greeks.

After 1930, wavering among American and European musical influences as well as the Greek musical tradition, the Greek composers begin to write music using the tunes of the tango, the samba, and the waltz combined with melodies in the style of Athenian serenades' repertory.

Rebetiko

Rebetiko, plural rebetika, (Greek: ρεμπέτικο and ρεμπέτικα respectively), occasionally transliterated as Rembetiko, is a term used today to designate originally disparate kinds of urban Greek folk music which have come to be grouped together since the so-called rebetika revival, which started in the 1960s and developed further from the early 1970s onwards.

Definition and etymology

History

Initially a music associated with the lower classes, rebetiko later reached greater general acceptance as the rough edges of its overt subcultural character were softened and polished, sometimes to the point of unrecognizability. Then, when the original form was almost forgotten, and its original protagonists either dead, or in some cases almost consigned to oblivion, it became, from the 1960s onwards, a revived musical form of wide popularity, especially among younger people of the time.

Origins

Rebetiko probably originated in the music of the larger Greek cities, most of them coastal, in today's Greece and Asia Minor. In these cities the cradles of rebetiko were likely to be the taverna, the ouzeri, the hashish den, and the prison. In view of the paucity of documentation prior to the era of sound recordings it is difficult to assert further facts on the very early history of this music. There is a certain amount of recorded Greek material from the first two decades of the 20th century, recorded in Constantinople / Istanbul, in Egypt and in America, of which isolated examples have some bearing on rebetiko, such as in the very first case of the use of the word itself on a record label. But there are no recordings from this early period which gives an inkling of the local music of Piraeus such as first emerged on disc in 1931 (see above).

1922-1932

In the wake of the population exchange of 1923, huge numbers of refugees settled in Piraeus, Thessaloniki and other harbor cities. They brought with them both European and Ottoman musical elements and musical instruments, particularly Ottoman café music, but also, and often neglected in such accounts, a somewhat Italianate style with mandolins and choral singing in parallel thirds and sixths. Some of these musicians from Asia Minor were highly competent musicians who quickly became studío directors and A&R men for the major companies. From the middle of the 1920s a substantial number of Ottoman-style songs were recorded in Greece, whereas examples of Piraeus-style rebetiko song first reached shellac in 1931 (see above).

The 1930s

During the 1930s, the relatively sophisticated musical styles met with, and cross-fertilised, the more heavy-hitting local urban styles exemplified by the earliest recordings of Vamvakaris and Batis.

This historical process has led to a currently used terminology intended to distinguish between the clearly Asia Minor oriental style, often called "Smyrneïka", and the bouzouki-based style of the 1930s, often called Piraeus style.

By the end of the 1930s rebetiko had reached what can reasonably be called its classic phase, in which elements of the early Piraeus style, elements of the Asia Minor style, and clearly European elements, had fused to generate a genuinely syncretic musical form. Simultaneously, with the onset of censorship, a process began in which rebetiko lyrics slowly began to lose what had been their defining underworld character. This process extended over more than a decade.

In 1936, the 4th of August Regime under Ioannis Metaxas was established and with it, the onset of censorship. Some of the subject matter of rebetiko songs was now considered disreputable and unacceptable. During this period, when the Metaxas dictatorship subjected all song lyrics to censorship, song composers would rewrite lyrics, or practice self-censorship before submitting lyrics for approval. The music itself was not subject to censorship, although proclamations were made recommending the "europeanisation" of Turkish music, which led to certain radio stations banning "amanedes" in 1938, i.e. on the basis of music rather than lyrics. This was, however, not bouzouki music. The term amanedes, (sing. amanes, gr. αμανέδες, sing. αμανές) refers to a kind of improvised sung lament, in ummeasured time, sung in a particular dromos/makam. The amanedes were perhaps the most pointedly oriental kind of songs in the Greek repertoire of the time.

References to drugs and other criminal or disreputable activities now vanished from recordings made in Greek studios, to reappear briefly in the first recordings made at the resumption of recording activity in 1946. In the United States, however, a flourishing Greek musical production continued, with song lyrics apparently unaffected by censorship, (see below) although, strangely, the bouzouki continued to be rare on American recordings until after WWII.

The postwar period

Recording activities ceased during the Axis occupation of Greece during World War II (1941–1944), and did not resume until 1946; that year, during a very short period, a handful of uncensored songs with drug references were recorded, several in multiple versions with different singers.

Vassilis Tsitsanis now became a leading personality in rebetiko music. His musical career had started in 1936, and continued during the war despite the occupation. He was both a brilliant bouzouki player and a prolific composer, with hundreds of songs to his credit. After the war he continued to develop his style in new directions, and under his wing, singers such as Sotiria Bellou, Stella Haskil, Marika Ninou and Prodromos Tsaousakis made their appearance.

Parallel to the post-war career of Tsitsanis, the career of Manolis Chiotis took Greek popular music in more radically new directions. Chiotis was a bold innovator, importing South American rhythms such as the mambo, and concentrating on songs in a decidedly lighter vein than the characteristic ambiance of rebetiko songs. Perhaps most significantly of all, Chiotis, himself a virtuoso not only on the bouzouki but on guitar, violin and outi (oud), was responsible for introducing and popularizing the modified 4-course bouzouki (tetrahordho) in 1956. Chiotis was already a seemingly fully-fledged virtuoso on the traditional 3-course instrument by his teens, but the guitar-based tuning of his new instrument, in combination with his playful delight in extreme virtuosity, led to new concepts of bouzouki playing which came to define the style used in laïki mousiki and other forms of bouzouki music which could no longer really be called rebetiko in any sense.

A comparable development also took place on the vocal side. In 1952 a young singer named Stelios Kazantzidis recorded a couple of rebetika songs that were quite successful. Although he would continue in the same style for a few years it was quickly realized, by all parties involved, that his singing technique and expressive abilities were too good to be contained within the rebetiko idiom. Soon well-known composers of rebetika—like Kaldaras, Chiotis, Klouvatos—started to write songs tailored to Stelios powerful voice and this created a further shift in rebetika music. The new songs had a more complex melodic structure and were usually more dramatic in character. Kazantzidis went on to become a star of the emerging laika music.

Kazantzidis, however, did not only contribute to the demise of classical rebetika (of the Piraeus style that is). Paradoxically he was also one of the forerunners of its revival. In 1956 he started his cooperation with Vassilis Tsitsanis who, contrary to the previously mentioned composers, did not write new songs for Kazantzidis but instead gave him some of his old ones to reinterpret. Kazantzidis, thus, sung and popularized such rebetika classics as "Synnefiasmeni Kyriaki", "Bakse tsifliki" and "Ta Kavourakia". These songs, and many others, previously unknown to the wide public suddenly became cherished and sought-after.

Interestingly, at about the same time many of the old time performers—both singers and bouzouki players—abandoned the musical scene of Greece. Some of them died prematurely (Haskil, Ninou), others emigrated to the USA (Binis, Evgenikos, Tzouanakos, Kaplanis), while some just quit music life for other work (Pagioumtzis, Genitsaris). This, of course, created a void which had to be filled with new "blood". In the beginning the new recruits—like for example Kolokotronis, Grey, and Kazantzidis—stayed within the bounds of classical rebetica. Soon, however, their youthful enthusiasm and different experiences found expression in new stylistic venues which eventually changed the old idiom.

This combined situation contributed, during the 1950s, to the almost total eclipse of rebetiko by other popular styles. In fact, somewhat confusingly, from at least the 1950s, during which period rebetiko songs were not usually referred to as a separate musical category, but more specifically on the basis of lyrics, the term "laïki mousiki" (λαϊκή μουσική), or "laïka", (λαϊκα) covered a broad category of Greek popular music, including songs with bouzouki, and songs that today would without doubt be classified as rebetiko. The term in its turn derives from the word laos (λάος) which translates best as "the people".

The revival of rebetiko

The first phase of the rebetiko revival can perhaps be said to have begun around 1960. In that year the singer Grigoris Bithikotsis recorded a number of songs by Markos Vamvakaris, and Vamvakaris himself made his first recording since 1954. During the same period, writers such as Elias Petropoulos began researching and publishing their earliest attempts to write on rebetiko as a subject in itself. The bouzouki, unquestioned as the basic musical instrument of rebetiko music, now began to make inroads into other areas of Greek music, not least due to the virtuosity of Manolis Chiotis. From 1960 onwards prominent Greek composers such as Mikis Theodorakis and Manos Hatzidakis employed bouzouki virtuosi such as Manolis Chiotis, Giorgios Zambetas, and Thanassis Polyhandriotis in their recordings.

The next phase of the rebetiko revival can be said to have started in the beginning of the 1970s, when LP reissues of 78 rpm recordings, both anthologies and records devoted to individual artists, began to appear in larger numbers. This phase of the revival was initially, and is still to a large extent, characterized by a desire to recapture the style of the original recordings, whereas the first phase tended to present old songs in the current musical idiom of Greek popular music, laïki mousiki. Many singers emerged and became popular during this period. It was during the 1970s that the first work which aimed at popularizing rebetiko outside the Greek language sphere appeared and the first English-language academic work was completed.

During the 1970s a number of older artists made new recordings of the older repertoire, accompanied by bouzouki players of a younger generation. Giorgios Mouflouzelis, for example, recorded a number of LPs, though he had never recorded during his youth in the 78 rpm era. The most significant contribution in this respect was perhaps a series of LPs recorded by the singer Sotiria Bellou, who had had a fairly successful career from 1947 onwards, initially under the wing of Tsitsanis. These newer recordings were instrumental in bringing rebetiko to the ears of many who were unfamiliar with the recordings of the 78 rpm era, and are still available today as CDs.

An important aspect of the revival of the late 1960s and early 1970s was the element of protest, resistance and revolt against the military dictatorship of the junta years. This was perhaps because rebetiko lyrics, although seldom directly political, were easily construed as subversive by the nature of their subject matter and their association in popular memory with previous periods of conflict.

Today, rebetiko songs are still popular in Greece, both in contemporary interpretations which make no attempt to be other than contemporary in style, and in interpretations aspiring to emulate the old styles. The genre is a subject of growing international research, and its popularity outside Greece is now well-established.

The word rebetiko/rebetika is generally assumed to be an adjectival form derived from the Greek word rebetis (ρεμπέτης). The word rebetis is nowadays construed to mean a person who embodies aspects of character, dress, behavior, morals and ethics associated with a particular subculture. The word is closely related, but not identical in meaning, to the word mangas (μάγκας). The etymology of the word rebetis remains the subject of dispute and uncertainty; an early scholar of rebetiko, Elias Petropoulos, and the modern Greek lexicographer Giorgos Babiniotis, both offer various suggested derivations, but leave the question open.

Musical bases of rebetiko

Although nowadays treated as a single genre, rebetiko is, musically speaking, a synthesis of elements of European music, the music of the various areas of the Greek mainland and the Greek islands, Greek Orthodox ecclesiastical chant, often referred to as Byzantine music, and the modal traditions of Ottoman art music and café music.

Melody and harmony

The melodies of most rebetiko songs are thus often considered to follow one or more dromos (δρόμος) or dromoi (δρόμοι), (in Greek, roads or routes). The names of the dromoi are derived in all but a few cases from the names of various Turkish modes, known in Turkish as makam.

However, the majority of rebetiko songs have been accompanied by instruments capable of playing chords according to the Western harmonic system, and have thereby been harmonized in a manner which corresponds neither with conventional European harmony, nor with Ottoman art music, which is a monophonic form normally not harmonized. Furthermore, rebetika has come to be played on instruments tuned in equal temperament, in direct conflict with the more complex pitch divisions of the makam system.

During the later period of the rebetiko revival there has been a cultural entente between Greek and Turkish musicians, mostly of the younger generations. One consequence of this has been a tendency to overemphasize the makam aspect of rebetiko at the expense of the European components and, most significantly, at the expense of perceiving and problematizing this music's truly syncretic nature.

However, it is important to note in this context that a considerable proportion of the rebetiko repertoire on Greek records until 1936 was not dramatically different from Ottoman café music, except in terms of language and musical "dialect". This portion of the recorded repertoire was played almost exclusively on the instruments of Ottoman café music, such as oud, kanonaki (Turkish kanun), violin, santouri (Turkish santur), tsimbalo (gr. τσίμπαλο), actually identical with the Hungarian cimbalom, politikí lyra (gr. πολιτικί λύρα), violoncello, and clarinet.

Taxim

There is one component within the rebetiko tradition which is common to many musical styles within Arabo-Turkish musical spheres. This is the freely improvised unmeasured prelude, within a given dromos/makam, which can occur at the beginning or in the middle of a song. This is known in Greek as taxim or taximi (gr.ταξίμ or ταξίμι) after the Arabic word usually transliterated as taqsim, and written taksim in Turkish.

Rhythms

Most rebetiko songs are based on traditional Greek or Anatolian dance rhythms. Most common are:

- Zeibekiko, a 9/4 or 9/8 meter, in its various forms,

- Hasapiko, a 4/4 meter and the fast version Hasaposerviko in a 2/4 meter,

- Anatolitiko or Bayo, a Bolero like 4/4 meter

Somewhat less common are:

- Tsifteteli, a 4/4 meter,

- Karsilamas and Argilamas, another 9/8 meter,

- Syrtos - general name for many dances, mostly 4/4 meter in various forms.

Various other rhythms are used very occasionally.

Lyrics

Like several other urban subcultural musical forms such as the blues, flamenco, fado, and tango, rebetiko grew out of particular urban circumstances. Oftentimes, but by no means always, its lyrics reflect the harsher realities of a marginalized subculture's lifestyle. Thus one finds themes such as crime, drink, drugs, poverty, prostitution and violence, but also a multitude of themes of relevance to people of any social stratum: death, eroticism, exile, exoticism, disease, love, marriage, matchmaking, the mother figure, war, work, and diverse other everyday matters, both happy and sad.

The womb of rebetika was the jail and the hash den. It was there that the early rebetes created their songs. They sang in quiet, hoarse voices, unforced, one after the other, each singer adding a verse which often bore no relation to the previous verse, and a song often went on for hours. There was no refrain, and the melody was simple and easy. One rebetis accompanied the singer with a bouzouki or a baglamas (a smaller version of the bouzouki, very portable, easy to make in prison and easy to hide from the police), and perhaps another, moved by the music, would get up and dance. The early rebetika songs, particularly the love songs, were based on Greek folk songs and the songs of the Greeks of Izmir and Istanbul.

– Elias Petropoulos

Manos Hatzidakis summarized the key elements in three words with a wide presence in the vocabulary of modern Greek meraki, kefi, and kaimos (μεράκι, κέφι, καημός: love, joy, and sorrow).

A perhaps over-emphasized theme of rebetiko is the pleasure of using drugs, especially hashish. Rebetiko songs emphasizing such matters have come to be called hasiklidika (χασικλίδικα), although musically speaking they do not differ from the main body of rebetiko songs in any particular way.

Instruments of rebetiko

The first rebetiko songs to be recorded, as mentioned above, were mostly in Ottoman style, employing instruments of the Ottoman tradition. During the second half of the 1930s, as rebetiko music gradually acquired its own character, the bouzouki began to emerge as the emblematic instrument of this music, gradually ousting the instruments which had been brought over from Asia Minor.

The bouzouki

The bouzouki was apparently not particularly well-known among the refugees from Asia Minor, but had been known by that name in Greece since at least 1835, from which year a drawing by the Danish artist Martinus Rørbye has survived. It is a view of the studio of the Athens luthier Leonidas Gailas (Λεωνίδας Γάϊλας), whom the artist describes as Fabricatore di bossuchi. The drawing clearly shows a number of bouzouki-like instruments. Despite this evidence, we still know nothing of the early history of instrument's association with what came to be called rebetiko.

Although known in the rebetiko context, and often referred to in song lyrics, well before it was allowed into the recording studio, the bouzouki was first commercially recorded not in Greece, but in America, in 1926. The first recording to feature the instrument clearly in a melodic role, was made in 1929, in New York. Three years later the first true bouzouki solo was recorded by Ioannis Halikias, also in New York, in January 1932.

In Greece the bouzouki had been allowed into a studio for the very first time a few months previously, in October 1931. In the hands of Giorgios Manetas, together with the tsimbalo player Yiannis Livadhitis, it can be heard accompanying the singers Konstantinos Masselos, aka Nouros, and Spahanis, on two discs, three songs in all. However, it was a whole year later, in October 1932, in the wake of the success of Halikias' New York recording, which immediately met with great success in Greece, that Markos Vamvakaris made his first recordings with the bouzouki. These recordings marked the real beginning of the bouzouki's recorded career in Greece, a career which continues unbroken to the present day.

Other instruments

The core instruments of rebetiko, from the mid-1930s onwards, have been the bouzouki, the baglamas and the guitar. Instruments characteristic of the Ottoman café style Greek songs included accordion, clarinet, kanonaki, oud, santouri, tambourine, tsimbalo, or cimbalom, violin, violoncello, accordion, politiki (Constantinople) lyra, and finger-cymbals. Several of these instruments were also used in rebetiko songs of other than Ottoman character. Other instruments heard on rebetiko recordings include: Cretan lyra, double bass, laouto, mandola, mandolin and piano. In some recordings, the sound of clinking glass may be heard. This sound is produced by drawing worry beads (komboloi) against a fluted drinking glass, originally an ad hoc and supremely effective rhythmic instrument, probably characteristic of teké and taverna milieux, and subsequently adopted in the recording studios.

Éntekhno

Drawing on rebetiko's westernization by Tsitsanis and Chiotis, Éntekhno arose in the late 1950s. Éntekhno (lit. meaning 'art song') is orchestral music with elements from Greek folk rhythm and melody; its lyrical themes are often political or based on the work of famous Greek poets. As opposed to other forms of Greek urban folk music, éntekhno concerts would often take place outside a hall or a night club in the open air. Mikis Theodorakis and Manos Hadjidakis were the most popular early composers of éntekhno song cycles. Other significant Greek songwriters included Stavros Kouyoumtzis, Manos Loïzos, and Dimos Moutsis. Significant lyricists of this genre are Manos Eleftheriou, and poet Tasos Livaditis. By the 1960s, innovative albums helped éntekhno become close to mainstream, and also led to its appropriation by the film industry for use in soundtracks. A form of éntekhno which is even closer to Western Classical music was introduced during the late 1970s and 1980s by Thanos Mikroutsikos. (See the section 'Other popular trends' below for further information on Néo kýma and Contemporary éntekhno.)

Laïkó

Laïkó (λαϊκό τραγούδι 'song of the people' or αστική λαϊκή μουσική 'urban folk music'), also known today as classic laïkó (κλασικό/παλιό λαϊκό), was the mainstream popular music of Greece during the 50s and 60s. As it was the case with éntekhno, laïkó emerged after the popularization of rebetiko; but the musical style and lyrical themes of classic laïkó songs were far more orientalized and can be compared with Turkey's fantezi songs. The influence of oriental music on laïkó can be most strongly seen in 1960s indoyíftika (ινδογύφτικα) 'indian gypsy (songs)' (or ινδοπρεπή 'indian-like'), which can be described as filmi with Greek lyrics. Manolis Angelopoulos was the most popular indoyíftika performer, while pure laïkó (colloquially known as Mournful laïkó - Βαρύ (lit. 'heavy') λαϊκό) was dominated by superstars such as Stelios Kazantzidis and Stratos Dionysiou. The more cheerful version of laïkó, called elafró laïkó (ελαφρολαϊκό - elafrolaïkó 'light laïkó'), was often used in musicals during the Golden Age of Greek cinema.

Among the most significant songwriters and lyricists of this category are considered Akis Panou, George Zambetas, Apostolos Kaldáras, Giorgos Mitsakis, Babis Bakális, Giannis Papaioannou, and Eftichia Papagianopoulos. Many artists have combined the traditions of éntekhno and laïkó with considerable success, such as the composers Mimis Plessas, Stavros Xarchakos, and Giorgos Mouzakis, and the lyricist Lefteris Papadopoulos.

During the same era, there was also another kind of soft music (ελαφρά μουσική, also called ελαφρό - elafró 'soft (song)', literally 'light') which became fashionable; it was represented by ensembles of singers/musicians such as the Katsamba Brothers duo, the Trio Kitara, the Trio Belcanto, and the Trio Athene. The genre's sound was an imitation of the then contemporary Cuban and Mexican folk music but also had elements from the early Athenian popular songs.

Laïkó in its original form eventually declined in popularity in the mid 1970s. Today, its tradition survives in the form of Éntekhno laïkó (Έντεχνο λαϊκό).

Modern laïká

Modern laïká or Laïká (not to be confused with the Laïkó genre) is currently Greece's mainstream music.

Laïká songs usually take the form of a sentimental ballad, in which case rock, and folk instrumentation is used, but they may also be closer to Western dance pop music (the latter type of laïká songs is referred to as laïkο-pop - λαϊκο-πόπ).

The term modern laïká comes from the phrase μοντέρνα λαϊκά (τραγούδια) 'modern songs of the people.' Laïká emerged as a style in the early 1980s. An indispensable part of the laïká culture is the písta - πίστα (pl.: πίστες) 'dance floor/venue' (formerly known as λαϊκό πάλκο 'folk palcoscenico, folk stage'), a specific type of night club (akin to the type of folk music club that exists in most Balkan countries) featuring live performances. Night clubs at which the DJs play only laïká are colloquially known as ellinádhika - ελληνάδικα. The main dances accompanying laïká are tsifteteli (on the table) τσιφτετέλι (πάνω σε τραπέζι) (typically for women), zeibekiko ζεϊμπέκικο (typically for men), and hasapiko χασάπικο (typically for groups of two or three people holding each other's shoulders).

Due to the considerable influence popular Greek music has from Turkey and the Middle East, there have been exchanges of musical themes, and several duets of Greek singers with singers from these areas during the 2000s; Greek singers like Sarbel have translated songs from Arabic to Greek that have become extremely popular. Also, with the latest Greek-Turkish relations warming, there have been written songs by composers from either of the two countries that are sung as a duet in both languages. A good example of a song crossing the three cultures is the song Anavis Foties by Despina Vandi which has been adapted into Arabic by Fadel Shaker (Dehket Al-Donya), and also has been adapted as a Turkish-Greek duet (entitled Aşka Yürek Gerek) performed by Mustafa Sandal, a popular singer from Turkey, and Greek singer Natalia Doussopoulos.

Renowned songwriters of modern laïká include Alekos Chrysovergis, Nikos Karvelas, Phoebus, Nikos Terzis, and the Pegasos duo (Antonis and Dimitris Paravomvolakis). Renowned lyricists include Giorgos Theofanous, Evi Droutsa, and Natalia Germanou.

In effect, there is no single name for modern laïká in the Greek language, but it is often formally referred to as σύγχρονο λαϊκό ([ˈsiŋxrono laiˈko]), a term which is however also used for denoting newly composed songs in the tradition of "proper" Laïkó; when ambiguity arises, σύγχρονο ('contemporary') λαϊκό or disparagingly λαϊκο-ποπ ('folk-pop', also in the sense of "westernized") is used for the former, while γνήσιο ('genuine') or even καθαρόαιμο ('pureblood') λαϊκό is used for the latter. The choice of contrasting the notions of "westernized" and "genuine" may often be based on ideological and aesthetic grounds.

Note: In this article, there has been employed a less charged terminology where the word Laïkó (short for παλιό λαϊκό) is reserved for the traditional genre of Greek urban folk music, while the word Laïká (short for μοντέρνα λαϊκά) is used as a technical term to denote the style of urban folk music originating in the 1980s.

Despite its immense popularity, the genre of modern laïká (especially laïkο-pop) has come under scrutiny for "featuring musical clichés, average singing voices and slogan-like lyrics" and for "being a hybrid, neither laïkó, nor pop".

Tsiftetéli

Tsiftetéli is a type of music that was brought over by refugees from Asia Minor in the 1920s. It can be described as the Greek version of belly dance music. The Arabic and Turkish influence on this type of music is very clear, and adds to the cultural similarities Greeks have with the Middle East. Tsiftetéli is a very popular style of Modern Greek music, and notable modern laïká artists, such as Katy Garbi, Anna Vissi, Despina Vandi, Eleni Karousaki, and Giorgos Mazonakis, have frequently included it in their music.

Skyládiko

Skyládiko (or Skyládika) is the byname of the Greek variation of Arabesque and Balkan pop folk music.

The general popularity of skyládiko in Greece is considered to be associated with the recent rise in popularity of several so-called "trash" or "decadent" (παρακμιακοί) singers such as Efi Thodi, Vera Labrou, and Stella Bezantakou, and with the 2007 music chart success of several tabloid talk show participants' singles (see Nikos Katelis for further information).

Skyládiko is akin to the Serbian Turbo-folk and Bulgarian Chalga, since all of them feature the same sort of balkan folk melodies (including Romani and Arabesque influences) combined with dance music, and share a distinctive kitch aesthetic. The same thing cannot be said with equal certainty for modern laïká, since the stylistic origins of the latter are slightly more varied than the ones of skyládiko; laïká originates in classic laïkó ballad, pop ballad, dance pop, arabesque love songs, and tsiftetéli.

Other popular trends

Folk singer-songwriters (τραγουδοποιοί) first appeared in the 1960s after Dionysis Savvopoulos' 1966 breakthrough album Fortighó. Many of these musicians started out playing Néo kýma, "New wave" (not to be confused with New Wave rock), a mixture of éntekhno and chansons from France. Savvopoulos mixed American musicians like Bob Dylan and Frank Zappa with Macedonian folk music and politically incisive lyrics. In his wake came more folk-influenced performers like Arleta, Mariza Koch, and Kostas Hatzis. This short-lived music scene flourished in a specific type of boîte de nuit called bouát (μπουάτ).

A notable musical trend in the 1970s (during the Junta of 1967–1974 and a few years after its end) was the rise in popularity of the topical songs (πολιτικό τραγούδι "political song"). Classic éntekhno composers associated with this movement include Mikis Theodorakis, Thanos Mikroutsikos, Giannis Markopoulos, and Manos Loïzos.

Nikos Xydakis, one of Savvopoulos' pupils, was among the people who revolutionized laïkó by using orientalized instrumentation. His most successful album was 1987's Kondá sti Dhóxa miá Stigmí, recorded with Eleftheria Arvanitaki.

Thanasis Polykandriotis, laïkó composer and classically trained bouzouki player, became renowned for his mixture of rebetiko and orchestral music (as in his 1996 composition "Concert for Bouzouki and Orchestra No. 1").

A popular trend since the late 1980s has been the fusion of éntekhno (urban folk ballads with artistic lyrics) with pop / soft rock music (έντεχνο ποπ-ροκ). Moreover, certain composers, such as Dimitris Papadimitriou have been inspired by elements of the classic éntekhno tradition and written songs cycles for singers of contemporary éntekhno music, such as Fotini Darra. The most renowned contemporary éntekhno (σύγχρονο έντεχνο) lyricist is Lina Nikolakopoulou.

There are however other composers of instrumental and incidental music (including filmscores and music for the stage), whose work cannot be easily classified, such as Giannis Markopoulos, Stamatis Spanoudakis, Giannis Spanos, Giorgos Hatzinasios, Giorgos Tsangaris, Nikos Kypourgos, Nikos Mamangakis, Eleni Karaindrou, and Evanthia Remboutsika. Vangelis and Yanni were among the few Greek instrumental composers who became internationally renowned; their work however had little influence on the tradition of Greek instrumental music.

Regarding "purely western" pop music, even though it has always had a considerable amount of listeners supporting it throughout the history of the post 1960s Greek music, it has only very recently (late 2000s) reached the popularity of laïkó/laïká, and there is a tendency among many urban folk artists to turn to more pop-oriented sounds.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

[en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Music_of_Greece,

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greek_folk_music,

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rebetiko].

Wikipedia® is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License.

Date: February 2011.

Photo Credits:

(1) Europe (by FolkWorld);

(2) Greek Colours (unknown);

(3) Greek Goddess with Tambourine,

(9)-(10) 3- & 4-Course Bouzoukis,

(14) Wikipedia Logo (by Wikipedia);

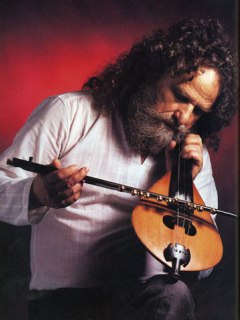

(4) Psarantonis,

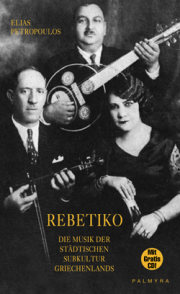

(7) Petropoulos 'Rebetiko - Die Musik der städtischen Subkultur Griechenlands',

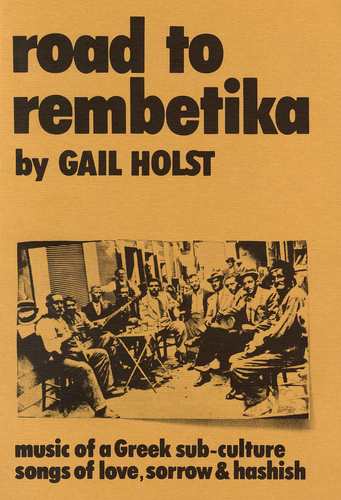

(8) Holst 'Road to Rembetika - Music of a Greek Sub-Culture, Songs of Love, Sorrow and Hashish'

(11) Eleftheria Arvanitaki,

(12) Savina Yannatou,

(13) Daemonia Nymphe

(from website);

(5)-(6) Musician Postcards (by Radio Tirana).

FolkWorld - Home of European Music

Layout & Idea of FolkWorld © The Mollis - Editors of FolkWorld

Layout & Idea of FolkWorld © The Mollis - Editors of FolkWorld