Angeline Morrison is a British musician, born in Birmingham to a Jamaican mother and a father from the Outer Hebrides.

In 2002 she gained a PhD from the University of Plymouth with a thesis on blankness, silence and racial binarism.

Morrison's 2022 album The Brown Girl and Other Folk Songs s a stripped-down collection of traditional songs, including

the Child ballads »The Maid and the Palmer«, »The Cruel Mother«, »Lizie Wan«, and last but not least »The Brown Girl«.

The famous Planxty version was my first experience of this intriguing ballad,[25]

and it has stayed with me. The ballad is very ancient, with early Scandinavian versions where the woman does penance in the wilderness for many years. Apparently it was not collected orally in the UK or Ireland until Tom Munnelly heard it sung by John Reilly in Boyle, Co. Roscommon. In this version, the woman seems to hold her hands up to the accusation of infanticide—but where incest is concerned, she is clear about her innocence.

—Angeline Morrison

"The Maid and the Palmer" (alternate versions are known as "The Maid of Coldingham" and "The Well Below The Valley"; original title in Percy "Lillumwham") (Roud 2335, Child ballad 21) is an English language murder ballad with supernatural/religious overtones. Because of its dark and sinister lyrics (implying murder and, in some versions, incest), the song was often avoided by folk singers. Child's main text in English comes from the seventeenth century ballad collection compiled by Thomas Percy, supplemented by a nineteenth century fragment recalled by Sir Walter Scott, although both Child and later scholars agree that the English language version(s) of the ballad derive from an earlier Continental original or "Magdalene ballad" that is based upon a medieval legend associated with Mary Magdalene, in which her story has become conflated with that of the Samaritan woman at the well in the Gospel of John. The ballad was present in oral tradition in Scotland in the early years of the nineteenth century but was subsequently lost there, however (to the astonishment of ballad scholars) versions have since been recovered in Ireland, in particular among the Irish Traveller community, with an intervening gap of some 150 years. A small fragment of the ballad has also been claimed to have been recovered in the U.S.A., but the veracity of this record is disputed. The "palmer" of Child's title, as included the Percy MS version, refers to a pilgrim, normally from Western Europe, who had visited the holy places in Palestine and who, as a token of his visits to the Holy Land, brought back a palm leaf or a palm leaf folded into a cross (refer Palmer (pilgrim)). In the ballad the palmer, as a holy man, has the ability to see the Magdalene character/protagonist's past in which she has borne and buried numerous children (nine in the Percy MS version) and to prescribe what fate awaits her in the hereafter, in the form of a set of seven year penances following which she will be absolved from her sins; in Continental versions, and in one variant collected in Ireland, the palmer is in fact Jesus.

A palmer (pilgrim) begs a cup from a maid who is washing at the well, so that he could drink from it. She says she has none. He says that she would have, if her lover came. She swears she has never had a lover. He says that she has borne nine babies (or in different versions, other numbers such as seven or five) and tells her where she buried the bodies. She begs some penance from him. He tells her that she will be transformed into a stepping-stone for seven years, a bell-clapper for seven, and spend seven years in hell.

In some variants, the children were incestously conceived.

This ballad combines themes from the Biblical stories of the Samaritan woman at the well, and Mary Magdalene. In several foreign variants, the palmer is in fact Jesus. Mary Diane McCabe, cited below, says that John Reilly was reportedly aware that the story concerned Mary Magdalene (McCabe, chapter 10, note 25, citing "A letter to me from Tom Munnelly dated 12 April 1978"), although whether this was before or following a suggestion by Munnelly is not recorded, while other sources cite Munnelly reporting that John Reilly also identified the palmer (termed "a gentleman" in his version) as Christ; another (thus far) unique, additional Irish variant collected by Munnelly from Willie A. Reilly, another traveller, specifically identifies the stranger as Christ: "Oh, for I am the Lord that rules on high / Green grows the lily-O / Oh, I am the Lord that rules on high / In the well below the valley-O" (McCabe, listed as version E, stanza 5).

A Breton variant of the song is called "Mari Kelenn" (also "Mari Gelan"; French: "Marie Quelenn" or "Gelen"); in this version, the element of meeting at the well is missing, and there is more emphasis on the penance that must be performed by the woman, plus the method of her ultimate absolution.

By analogy with its European counterparts, it seems clear that Child 21 is a British "Magdalene ballad", although the identity of the protagonist has been lost. Mary Diane McCabe, who corresponded extensively with the Irish collector Tom Munnelly regarding this and other ballads, regarded it as such and wrote:

Though all extant versions of the British Magdalen ballad are corrupt, the song is very effective. The irony of the Magdalen's religious oath and futile attempt to deceive the palmer would be fully appreciated only if the ballad audience already know the legend of the Magdalen, or the gospel story of the Samaritan woman. The enormity of the Magdalen's crime, the relentless revelation of the burial places she had supposed secret, and the horrified exclamation on the pains of hell remain mysterious but powerful even when the medieval legend has been forgotten. The original British Magdalen ballad, like its Scandinavian counterpart, tempered justice with mercy in the Sacrament of Penance, and the medieval audience was thus both entertained and instructed.

A more extensive account of the European (specifically: Finnish) counterpart/s of the song and its apparent history is contained in a 1992 thesis by Ann-Mari Häggman entitled "Magdalena på källebro : en studie i finlandsvensk vistradition med utgångspunkt i visan om Maria Magdalena" ("Magdalena at the wellspring: a study in the Finnish-Swedish song tradition based on the poem about Maria Magdalena") and in the Finnish Folklore Atlas, the latter of which states that "the song has been thought to originate in Catalonia, from where it spread to France, Italy and among Slavic peoples" (Finnish Folklore Atlas, pp. 611–612).

Writing in 1984, David C. Fowler presents an analysis of various aspects of the ballad, suggesting that the well at which the action is located may be a derivation from Jacob's Well, scene of the biblical conversation between Jesus and the Samaritan woman, that the inclusion of the figure of the palmer (archaic by the time of Percy) lends considerable antiquity to the text, and that the "Lillumwham" and other apparent nonsense lines in the Percy version appear to be later, and highly incongruous, grafts to the original verses. He also is of the opinion - in contrast to that of other scholars, who emphasise the "redemptive" potential of the penances - that the proposed penances could actually be intended to be ironic (along the lines of "when hell freezes over", etc.), in which case redemption would likely be never attainable for the protagonist.

A different ballad "The Cruel Mother", Child ballad 20, exists in a number of variants, in some of which there are verses where the dead children tell the mother she will suffer a number of penances each lasting seven years; those verses properly belong in "The Maid and the Palmer".

For this ballad, Child had access to only two English text versions without tunes (although he also quotes from translations of Continental equivalents), one longer one with 15 verses stated as being from p. 461 of the Percy Manuscript, plus another fragment with 3 verses only, recalled by none other than Sir Walter Scott, dating from the seventeenth century or before in the case of the Percy version. In Percy it appears under the name "Lillumwham", a possible nonsense word that appears in Percy's (and thus Child's) quoted refrain for each verse: "Lillumwham, lillumwham! Whatt then? what then? Grandam boy, grandam boy, heye! Leg a derry, leg a merry, met, mer, whoope, whir! Driuance, larumben, grandam boy, heye!". In an article "Songs connected with customs" published in 1915, A. G. Gilchrist, Lucy Broadwood and Frank Kidson suggested that these words may be related to the turning of a spinning wheel.

The fragment quoted by Child originating from Sir Walter Scott does not have the "Lillumwham" nonsense-style chorus but instead had a first refrain line that Scott did not recall, followed by a second, "And I the fair maiden of Gowden-gane". Unbeknown to Child, what appears to be a complete text of possibly the same version, with the refrain "The primrose o' the wood wants a name"/"I am the fair maid of Coldingham" (lines 2/4) had been collected at a similar time by the Reverend Robert Scott, minister of the parish of Glenbuchat in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, set down about 1818, under the name "The Maid of Coldingham", however this version remained in manuscript form and was not published until almost two centuries later, first appearing in Emily Lyle's 1994 Scottish Ballads compilation (as no. 32 in that collection) and then again in 2007 in The Glenbuchat Ballads by David Buchan and James Moreira, the latter work being a full transcription of the collection made by the Reverend Scott in the early part of the nineteenth century.

Unlike many other ballads that survived relatively prominently in oral tradition up to the twentieth century, this ballad appeared to be extinct in the British-Irish oral tradition until it was collected (in 2 versions) by Tom Munnelly from the repertoire of the Irish traveller John Reilly in the 1960s (see below), under the name "The Well Below The Valley"; in Reilly's version, the refrain is "Green grows the lily-o, right among the bushes-o", occurring after the third line of every verse which is always "...At the well below the valley-o". Munnelly transcribed the longer version where it appeared in Ceol: A Journal of Irish Music, III, No. 12 (1969), p. 66 and subsequently in B.H. Bronson's "The Traditional Tunes of the Child Ballads" (final volume, 1972). In his remarks on the song, Dr. Bronson states: "It was not to be expected that a traditional version of this ballad, which had barely survived in a fragmentary form in Scotland a century and a half ago, should have turned up in Ireland after the second world war. But such is the case, and we have word of yet another variant in the same vicinity in the year 1970...".

In fact, unknown to, and/or overlooked by both Munnelly and Bronson at the time, a "full text" of the Well Below the Valley variant had already been collected by Pádraig Ó Móráin in 1955 from Anna Ní Mháille, an old lady from Achill Island in County Mayo, with the opening verse:

There was a rider passin' by / There was a rider passing by / He askhed a drink, as he was dry / At the well below the valley, oh! / My washing tub it is afloat / Green grows the valley, oh!

(text reproduced in Anne O'Connor, "Child Murderess and Dead Child Traditions", Helsinki, 1991), while a shorter set of words (combined with the refrain from a separate song) had also been recorded, again in Ireland, by Seamus Ennis in 1954 from a different singer, Thomas Moran, and released (unrecognised since it was under a different title) on LP by Caedmon in 1961 (refer "Recordings").

Subsequent to his recording(s) of John Reilly, Munnelly also encountered versions of the song from two other travellers in different locations (all sharing the surname Reilly and possibly distantly related), as described further in the "Recordings" section, while a separate Irish revival singer and songwriter, Liam Weldon, recorded a partial version in the 1970s stated to have come from one Mary Duke, possibly also a traveller (additional discussion also below). Julia Power, a settled traveller resident in Dublin, also recalled the line "at the well down in the valley" (but no more) as part of a song, as recorded in Dublin in 2015-2016.

McCabe's thesis, pp. 392–396, also lists over 30 variants (labelled C.M.1 through C.M.32) of Child no. 20, "The Cruel Mother", in which either the seven year penances, or reference to being a porter in hell, occur, apparently as borrowings from the present ballad, comprising 12 from Scotland, 2 originally from Ireland (the informants in these cases then residing in England and the U.S.A.), 6 from Canada, and 12 from the U.S.A.

Despite its rarity in Britain, the ballad appears to have been popular and widely distributed elsewhere in Europe, in particular in the Finland/Sweden area, where - in the form known as "Mataleena" or "Magdalena på Källebro", clearly related to the figure of Mary Magdalen - a large number of performances have been documented. Although no complete version has been found in the United States, John Jacob Niles in his publication The Ballad Book reproduces three stanzas stated to have been collected in 1932 from a child in the Holcomb family in Kentucky, about nine years old, who "got the verses from an uncle", the first of which reads "Seven long years you shall atone / Derry leggo derry don / Your body be a steppingstone / Derry leggo derry downie" and which he identifies as a fragment of the present ballad, under the title that he assigns to it, "Seven Years", however it should also be noted that some more recent authors do not accept all of Niles' statements regarding ballads (or portions thereof) that he claimed to have discovered, especially in Kentucky, that have been reported by no-one else.

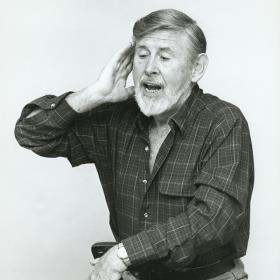

The Irish song collector Tom Munnelly was instrumental in popularising the song (under the title "The Well Below The Valley") in the 1970s folk revival, having heard it sung by John Reilly in County Roscommon in 1963. He recorded at least two versions from Reilly; the shorter version of the two, with ten verses, was released on Reilly's posthumous Topic LP The Bonny Green Tree (1978), also re-released on volume 3 of the 1998 Topic "Voice of the People" series, O'er His Grave the Grass Grew Green – Tragic Ballads. Prior to the official release of his Reilly recordings, Munnelly played his tape to (among others) Christy Moore who then used it as the title track to the 1973 "Planxty" album of the same name (see below). A more extensive, 1969 recording from Reilly (16 verses) exists in the tape collection of D. K. Wilgus, and can be heard via this youtube release. Earlier, in 1954, the song collector Seamus Ennis recorded singer Thomas Moran of Mohill, Co. Leitrim singing a partial version (6 verses only); in Moran's version (available for listening here) the refrain (lines 2 and 4 of each verse) appears to belong to a previous Child Ballad (number 20, "The Cruel Mother") but the remainder of the text is that of the present song. Mis-titled "The Cruel Mother", Moran's version was actually released earlier than Reilly's, on the 1961 Caedmon release The Folk Songs of Britain, Vol. IV: The Child Ballads 1 (TC1145), re-released under the same title as Topic 12T160 (1968).

Subsequent to hearing and recording the version/s by John Reilly, Tom Munnelly taped additional versions of the song (as "The Well Below The Valley") from two other singers in Ireland, a Willie A. Reilly aged 35 near Clones, Co. Monaghan in 1972, and a Martin Reilly aged 73 in Sligo, Co. Sligo in 1973; both were travellers and possibly related, but distantly, to John Reilly of Boyle. (Listed as M.P. [=Maid and Palmer] versions E and F in Mary Diane McCabe's 1980 thesis, pp. 391–392, based on copies of tapes supplied by Munnelly). The same author notes yet another version obtained by Irish revival singer Liam Weldon, stated as being "as learned from the singing of Mary Duke (a traveller?)"; Weldon is described elsewhere as having "a lifelong interest in the songs of the Irish Travelers". As performed by Weldon, Mary Duke's is only a partial version, comprising the initial encounter at the well between the protagonist and the "man riding by" but none of the subsequent revelations of child murders and associated penances.

"The Cruel Mother" (a.k.a. "The Greenwood Side" or "Greenwood Sidey") (Roud 9, Child 20) is a murder ballad originating in England that has since become popular throughout the wider English-speaking world.

According to Roud and Bishop:

A woman gives birth to one or two illegitimate children (usually sons) in the woods, kills them, and buries them. On her return trip home, she sees a child, or children, playing, and says that if they were hers, she would dress them in various fine garments and otherwise take care of them. The children tell her that when they were hers, she would not dress them so but murdered them. Frequently they say she will be damned for it.

Some variants open with the account that she has fallen in love with her father's clerk.

This ballad exists in a number of variants, in some of which there are verses where the dead children tell the mother she will suffer a number of penances each lasting seven years, e.g. "Seven years to ring a bell / And seven years porter in hell".

Those verses properly belong in "The Maid and the Palmer" (Child ballad 21).

Variants of "The Cruel Mother" include "Carlisle Hall", "The Rose o Malinde", "Fine Flowers in the Valley", "The Minister's Daughter of New York", and "The Lady From Lee", among others. "Fine Flowers of the Valley" is a Scottish variant. Weela Weela Walya is an Irish schoolyard version. A closely related German ballad exists in many variants: a child comes to a woman's wedding to announce himself her child and that she had murdered three children, the woman says the Devil can carry her off if it is true, and the Devil appears to do so.

Ballad scholar Hyder Rollins listed a broadside print dated 1638, and a fairly complete version was published in London in broadside ballad format as "The Duke's Daughter's Cruelty: Or the Wonderful Apparition of two Infants whom she Murther'd and Buried in a Forrest, for to hide her Shame" sometime between 1684 and 1695.

This ballad was one of 25 traditional works included in Ballads Weird and Wonderful (1912) and illustrated by Vernon Hill.

—Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Also known as Greenwood Sidey or The Lady of York, this ancient tale of infanticide and haunting can be found in various forms in the UK, Ireland, Denmark, Germany and the USA. It's one of those incredibly popular song stories that filter into children's games. Interestingly, the ballad references ancient beliefs that the revenant spirits of unbaptised children tended to be quite malicious. The wonderful Birmingham source singer Cecilia Costello recorded a version for the BBC in 1954, complete with a spoken introduction where she describes how her father would sing this to her as a warning. As I was a-walking Mrs Costello's lovely version, learning it to record here, this melody and all the recorder parts just swooshed into my head.

—Angeline Morrison

"Lizie Wan" is Child ballad 51 and a murder ballad. It is also known as "Fair Lizzie".

The heroine (called variously Lizie, Rosie or Lucy) is pregnant with her brother's child. Her brother murders her. He tries to pass off the blood as that of some animal he had killed (his greyhound, his falcon, his horse), but in the end must admit that he murdered her. He sets sail in a ship, never to return.

This ballad, in several variants, contains most of the ballad "Edward", Child 13.

Other ballads on this theme include "Sheath and Knife", "The King's Dochter Lady Jean", and "The Bonny Hind".

The Ballad of Lizie Wan was the inspiration for the title song from English recording artist Kate Bush's album The Kick Inside. It is directly referenced in an early demo recording of the song in the second verse: "You and me on the bobbing knee / Welling eyes from identifying with Lizie Wan's story."

The final version of the song replaces the direct reference and describes the ballad as "old mythology."

dark ambient version of the song, titled "Lucy Wan," appeared on the 1993 album Murder Ballads (Drift) by Martyn Bates and Mick Harris.

—Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This ballad makes no attempt to paint over the human potential for darkness and destruction. I learned this unusual version from the singing of the great Ewan MacColl, via YouTube. Also known as Lizie Wan, or Fair Lizzie, or Rosie Anne, this song was collected by Francis James Child, and included by Ralph Vaughan Williams and A.L Lloyd in their Penguin Book of English Folk Songs (1959). Ella Bull and W. Percy Merrick collected the song in 1904 from Mrs Charlotte Dann of Cottenham, Cambridgeshire. Kate Bush wrote her own version of this ballad, which she re-titled as The Kick Inside (1978).

—Angeline Morrison

The Brown Girl is Child ballad 295.

The brown-skinned girl received a letter from her lover, telling her that he was rejecting her for a more beautiful woman. Then she received another, saying he was dying and summoning her. She told him she was delighted at his dying.

Recorded by Dawn Landes for The 78 Project in the Brooklyn Botanic Garden on September 1, 2011.

This is on the Steeleye Span 1976 album Rocket Cottage.

—Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

I first learned The Brown Girl from the singing of Martin Carthy, though this version is from the singing of Frankie Armstrong.

This song always strikes me as more of a revenge fantasy than an attempted homicide. The brown girl in this version feels slightly less hot and angry than she does in others - but she still knows her worth.

I used to dream and wonder about whether the girl in this song might be my sort of brown (i.e., a person of colour). So this song was a sort of talisman for me, leaving a small space of possibility that I might find people like me in these songs. This song contains elements of ballads such as Barbara Allen, Lord Thomas & Fair Eleanor / Ellender...

Here the Brown Girl is wasting time, playing with leaves and flowers, chucking rockstone, daydreaming... basically taking as long as possible to reach the sickbed of her false love.

—Angeline Morrison

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License.

Date: November 2022.

Photo Credits:

(1),(3) Planxty,

(4),(7) Angeline Morrison,

(5) Maddy Prior,

(6) John Reilly,

(8) Ewan MacColl,

(9) Polly Paulusma,

(10) 'The New Penguin Book of English Folk Songs',

(11) Lucy Ward,

(12) Martin Carthy &

(13) Dave Swarbrick,

(14) Frankie Armstrong,

(15) A.L. Lloyd

(unknown/website);

(2) 'The Well Below the Valley'

(by 8notes.com).