FolkWorld Article by

Walkin' T:-)M:

T:-)M's Night Shift

Ireland & Macedonia - Traditional Music at the European Fringe

"Photographs of musicians adorn the wall; also displayed are poems by Junior

Crehan, the eighty-nine-year-old fiddler who has led these Sunday night sessions for

more than fifty years. When Junior Crehan was born in 1908, Gleesons was a smaller

establishment - a small pub in the farmhouse kitchen. Jimmy and Nell are now the

fourth generation of Gleesons to run the pub. Jimmy recalls that even in his

grandfather's days, there was always music. Every house nearly had some kind of

an instrument, mostly back then a fiddle or a concertina."

"Photographs of musicians adorn the wall; also displayed are poems by Junior

Crehan, the eighty-nine-year-old fiddler who has led these Sunday night sessions for

more than fifty years. When Junior Crehan was born in 1908, Gleesons was a smaller

establishment - a small pub in the farmhouse kitchen. Jimmy and Nell are now the

fourth generation of Gleesons to run the pub. Jimmy recalls that even in his

grandfather's days, there was always music. Every house nearly had some kind of

an instrument, mostly back then a fiddle or a concertina."

Dorothea Hast's and Stanley Scott's condensed but comprehensive

Music in Ireland (sorry, no cover picture available) starts with a description

of a typical Irish music session in Gleesons Pub in the tiny hamlet of Coore, West Clare

(which is, by the way, also home of flutist Kevin Crawford's parents).

During Junior Crehan's [-> FW#21]

childhood, dances were regular outdoor events at crossroads.

Music and dancing also took place on Sunday evenings at the Lenihan household in

nearby Knockbrack. The Lenihans always had the latest 78 rpm recordings of Irish

music from America; Junior would borrow one record each week, take it home, learn

the tunes, and exchange it for a new record the following Sunday.

Prior to 1936, Junior would frequently play for country dances in homes. Dances

were held for special occasions, such as wedding, holiday, or an American wake.

Dances were also held when a family would encounter some misfortune, like the

death of some cattle, and the charge of a few pennies' admission at the door helped

them recoup their losses. The Dance Halls Act of 1935 changed all that. Jimmy

Gleeson recalls: It was mostly run by parish priests and they made the country

dance illegal. It was all modern music - waltzes, quicksteps, and that kind of

stuff. It was a great way for the parish priests and the parish as a whole to

collect money.

To compete with the big bands performing in the church halls, traditional

musicians joined into large ensembles called ceili bands. For more informal

playing in smaller ensembles, traditional musicians met in pubs like Gleesons.

Junior was the central player. Jimmy Gleeson expanded his small pub to its

present size in 1978. The Sunday night sessions became a permanent fixture in

the new space. Junior's passing in 1998 marked the end of an era at Gleesons,

but the sesson continues on strongly today, incorporating new musicians and

hosted by the renowned accordion player, Jackie Daly.

The 1935 Dance Halls Act needs some more explanation which is unfortunatly not given by

the authors. However, quite understandable if you have to squeeze the whole story in a

short 150 pages volume.

Oxford's Global Music Series is

a set of case study volumes focused on specific cultures,

such as "Music in Bulgaria," "Music in East Africa" etc.

This volume obviously focuses on Irish traditional music -

forms of singing, instrumental music, and dance

that are closely interwoven with Ireland's rich cultural history.

Designed for the classroom, but not exclusively limited to it, it is

no tiresome academic lecture. Both authors have a deep affection for the subject,

and both practise the art of Irish music as well.

This volume obviously focuses on Irish traditional music -

forms of singing, instrumental music, and dance

that are closely interwoven with Ireland's rich cultural history.

Designed for the classroom, but not exclusively limited to it, it is

no tiresome academic lecture. Both authors have a deep affection for the subject,

and both practise the art of Irish music as well.

The book is meant as an introduction and an overview, focusing on

some chosen topics, e.g. the passing on of the tradition, the dance tunes, or

Gaelic languange sean-nos singing. The Goilin singers' club, a driving force

in promoting traditional Irish song, has been

founded in 1979 by Tim Dennehy (->

FW#24,

FW#28), and

I would like to cite a longer extract from the book.

Club member Jerry O'Reilly explains that the title goilin comes from two things:

an expression for singing in Connemara, and also an outlet from something out into

a bigger thing. And this is what we're endeavouring to do - pushing it out into the

mainstream of Irish life.

The Trinity Inn resounds with the energetic chatter of Dubliners beginning their weekend.

I [Scott] proceed up the stairs to a quieter room, where the singing will begin at ten o'clock.

I am greeted by Jerry O'Reilly's wife Anne, who chats with a friend while collecting

a small admission fee from each person who enters the session. A few minutes before the

singing starts, Jerry moves about and has a quiet word with two singers. He then asks

discretely if I would be willing to sing the second song of the night. To get the

evening rolling, the first three singers are prearranged.

I count fourteen women and twenty-four men, ranging in age from near twenty to

sixty-plus.

Instrumental accompanying is absent from sessions of the Goilin Singers'

Club. The emphasis is on songs handed down from generations of amateur singers, whose

intimate manner of unaccompanied singing places primary emphasis on details of phrasing,

ornamentation, and storytelling that can easily be lost when accompaniment is provided.

Melodically, many Irish tunes reveal a pitch logic that is modal rather than harmonic.

Rhythmically, Irish folk songs tend to be sung in free rhythm.

The first to sing is a young man, who sings a night-visit song in English. I

follow Pat's song of ill-fated love with a humorous love song. The third singer is

Nick O Murchu, who spent the previous weekend at the Clare Festival of Traditional

Singing. Nick begins a ballad entitled "Mary and the Russian Sailor," but after three

traditional verses the song mutates into a farcial contemporary account of a tennis

accident. At the Clare Festival, a singer named Mick Fowler (who is known for singing

"Mary and the Russian Sailor") ruptured his Achilles' tendon playing doubles with singer

Johnny Moynihan and Dora Hast. It is a mark of the vitality of the singing tradition

that a ballad about this event has already been composed and performed, less than a

week after the incident.

A young woman follows with a serious contemporary ballad by Scottish songwriter

Dick Gaughan [-> FW#25].

The next two songs relate to seasonal rituals: "Dancing at Whitsun," and "The Boys of

Barr na Sraide" [-> FW#28].

Irish Gaelic singing makes it first appearance in the following selection, a macaronic

composition. Macaronic songs are linguistic hybrids, in which verses alternate between

English and Irish. The macaronic song is succeeded by a recitation; Luke Cheevers

presents a humorous poem by Percy French entitled "Queen Victoria's After-Dinner Speech."

Luke's performance is lent further hilarity by a heckler, who punctuates his recitation

with critical comments and corrections. Luke's recitaion is followed by the macaronic

"Siuil a riun", which had great currency in the United states during the anti-Vietnam

war movement under the English title "Johnny Has Gone for a Soldier." The first half of

the evening then concludes with a delicate, florid sean-nos sung entirely in Gaelic.

After this song, Luke Cheevers announces that the newly published

The Age of Revolution in the Irish Song Tradition 1776 to 1815,

is available for sale. The editor of the book, Terry Moylan, sits beside Jerry O'Reilly.

The singers become more adventurous in the second half. Two sean-nos songs follow. Terry

Moylan then sings "I'm Done with Bonaparte." Terry has collected a large number of

pro-Bonaparte songs, "I'm Done with Bonaparte" breaks from this tradition by expressing

disappointment in the French republican-turned dictator. I am quite surprised when Terry

informs me that it was written by rock composer Mark Knopfler. Terry's singing is

succedded by a sean-nos, and then by the English language song "Wondrous Mayo,"

representing a very common Irish song genre: odes in praise of the Irish landscape.

In the penultimate song of the night, this stylistic dam [of sticking to

authentic repertoire] begins to burst, with the rendering of an American chain

gang song. Singers enthusiastically joing choruses of "Breakin' Rocks All Day on a

Chain Gang," and this communal spirit continues into group singing of the Gaelic choruses

of "I Spent a Year Down in Kilrush."

The accompanying CD features 28 tracks, among the before-mentioned artists

you may find singers as heterogeneous as tenor Count

John McCormack

and Joe Heaney,

Andy Irvine (-> FW#23) and

Padraigin Ni Uallachain (-> FW#24).

Taking Irish music to the Global Marketplace is illustrated by the

Riverdance show (-> FW#6), Celtic rockers

Black 47 (->

FW#20), and today's traditional supergroup

Lunasa (-> FW#29):

Listen to fiddler Michael Coleman's medley of "Dr. Gilbert" and "The Queen of May,"

accompanied by Herbert Henry on piano. It is a sprightly performance, with much

fiddle ornamentation in the form of triplets and rolls. Henry plays a simple

accompaniment, playing bass notes with his left hand on beats one and three, and

block chords with his right on beats two and four. The performance bounces along

at around 112 beats per minute, with a lilting, danceable rhythm.

Now listen to Lunasa's performance. The bassitron is an electric upright

bass, with a curved bridge that allows the player to play with a bow or pluck

with the fingers, and a streamlined body several times thinner than a conventional

double bass. The performance begins with Hutchinson bowing a low E, varying the

angle of his bow to create a rich variety of overtones, amplified by the electric

pickup to create an otherworldly, space-age ambience. Fiddler Sean Smyth plays

"Dr. Gilbert" faster than Michael Coleman, beginning at 126 beats per minute and

accelerating from there.

In the second verse, the bass rhythm becomes more pronounced, with strong accents

on one and three, while guitarist Donogh Hennessy chunks out a stream of chords,

two per beat. In the third verse, Hennessy's guitar places a strong accent on the

third beat in each measure, giving the performance a strong rock feeling.

After the third verse, the bass and guitar drop out as uilleann piper Cillian

Vallely plays the three-part reel "The Merry Sisters of Fate" in unison with fiddle

and flute. The final tune in the medley comes not from Ireland, but was adapted

from a suite recorded by Breton guitarist

Dan Ar Braz. It is in reel rhythm, but

the sections are unequal. The band plays the tune eight times through, treating it

quite freely. On the third and fourth verses, the pipes and flute add high drones

and harmonies; on the fifth and sixth verses, they add contrapuntal melodies and

counter-rhythms, riffing over the basic melody and chord progression.

Finally, lets hear what is said about the Irish harp:

The harp has appeared on Irish coinage since the twelfth century, illustrating the

central role of music as a symbol of Irish cultural identity. Harps were used to

accompany poems and songs praising the chieftains of the Irish Gaelic aristocracy.

Queen Elizabeth felt that itinerant poets and harpers were often political spies,

stirring up unrest through their lyrics. A statute of 1603 effectively banned the

playing of Irish music with a proclamation to hang the harpers wherever found

and destroy their instruments. The harping tradition declined as musicians

faced intimidation. The increasing impact of English colonial plantations led

to a breakdown of the Gaelic order, affecting the aristocratic harping tradition.

In the late eighteenth century, four festivals were organized as a means to

revitalize the waning harp tradition. The most famous took place in Belfast in

1792, attracting ten harpers as competitors.

Edward Bunting

(1773-1843) was

hired to notate the music performed over the course of the three-day event in order

to preserve this oral repertory in written form. The Belfast Harp Festival proved

to be a turning point in his life, leading to subsequent field-work with harpers

and traditional musicians throughout Ireland. He is reputed to be the first Irish

collector to get music directly from musicians in the field.

While the harp became an important symbol of Irishness by the nineteenth century,

the harping tradition itself became nearly extinct. It was not until the pioneering

work of Grainne Yeats in the 1950s and 1960s and Maire Ni Chathasaigh [->

FW#1,

FW#20]

in the 1970s that the harping tradition was revived.

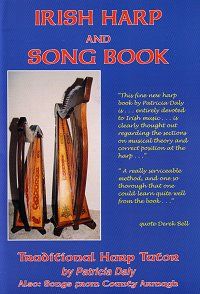

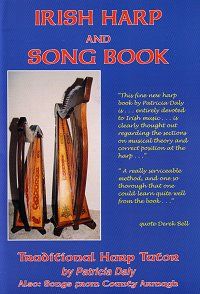

In the Edward Bunting county of Armagh the harping tradition is quite alive;

not at least due to the efforts of

Patricia Daly (->

FW#29).

The All-Ireland champion, performer and teacher

has been active on the harp circuit since joining the

Armagh

Pipers Club (-> FW#29)

in the 1970s; in 1996 she was a founder member of the

Armagh Harper's Association.

not at least due to the efforts of

Patricia Daly (->

FW#29).

The All-Ireland champion, performer and teacher

has been active on the harp circuit since joining the

Armagh

Pipers Club (-> FW#29)

in the 1970s; in 1996 she was a founder member of the

Armagh Harper's Association.

The Irish Harp and Song Book

which is both a harp tutor and tune collection, is intended to

guide the prospective harper from frustration to fulfillment.

As the late Chieftains

harper Derek Bell (-> FW#24)

says in the foreword, there is

no need to deal with a classical grounded teacher to learn traditional

music on the harp anymore. The publication starts from the scratch.

The first half of the fifty page volume introduces the pupil to

music theory and harp techniques, the second half contains twenty

tunes and songs.

It features a selection of Irish traditional dance music, There's old favourites

like the jig "Queen Of The Fair" (compare a recent recording ->

FW#29),

"Fred Finn's Reel" (-> FW#18)

or the "Moving Cloud Reel" (-> FW#29).

You can find a hornpipe such as

"Cross the Fence" (-> FW#26),

"Sonny's Mazurka (-> FW#18), and

Carolan tunes and slow airs like

"Blind Mary" (-> FW#21,

FW#28).

But there's also fresh stuff alike, I recommend to look for Patricia's own slow air

"The Magic of the White Swans" (-> FW#29).

Patricia has also collected a number of songs from her home area:

"Gosford's Fair Demesne" (-> FW#29)

is a love song from around 1800 that has been passed on in her husband's family;

the "Hiring Fair at Hamilton's Bawn" has been popular thoughout the North and

could recently heard here in Germany sung by Desi Wilkinson

(-> FW#20);

the "Rollicking Boys of Tandragee"

is a Colum Sands (->

FW#23,

FW#27) favourite.

Of course, "Phelim Brady, the Bard of Armagh"

(-> FW#22)

it quite well known. A story too good not to be told here:

Folklore has it that the Bard of Armagh's name was not Phelim Brady, but the Rev.

Doctor Patrick Donnelly. Patrick Donnelly was born in Dessertcrete in Co. Tyrone

and the family was evicted from their home because his father, a farmer, got into

disrepute with the landlord. Patrick then took up with an itinerant harper

called Phelim Brady and travelled the countryside until at the age of 13 or 14 he

boarded a ship for France. Patrick studied to become a medical doctor and later

answered his calling to priesthood. He was ordained and eventually consecrated

Bishop of Dromore. Life was difficult during these Penal Times in Ireland

and he carried out his ministry under the disguise of the old harper - Phelim

Brady. Continuing, under this disguise and detected for 18 years he died about

the year 1716 in Lower Killeavy.

The Scottish reel "Flowers of Edinburgh" is not featured in Patricia's harp tutor,

but recorded on her "Rolling Wave" album (->

FW#29).

And you can find it as tabulature in Ken Perlman's Eyerything You Wanted to

Know About Clawhammer Banjo, and this seems quite strange at first sight.

Clawhammer banjo and Celtic tunes?

The word clawhammer had supplanted frailing as the term-of-choice for

describing the method of banjo down-picking.

The Southern old-time revival scene has been dominated for over two decades by players

who emulate a very specific fiddling-banjo picking style from the Galax/Mt. Airy region

on the Virginia-North Carolina border. This style features a highly exaggerated back

beat, swing treatment of eighth notes akin to that found in bluegrass and jazz,

and the overall primacy of rhythmic drive over melody.

By the 1970s a definite split had developed among active clawhammer banjo players.

Two camps grew up, which ultimately became known respectively as traditional

clawhammer and melodic clawhammer.

Our aim was to create a style of clawhammer that was essentially a full-fledged solo

instrumental style. It would give the banjoist the ability to play a large range of

musical genres with speed, accuracy, power, and a wide range if expression.

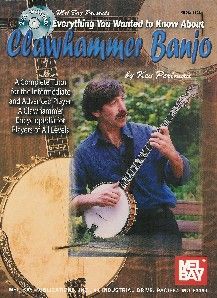

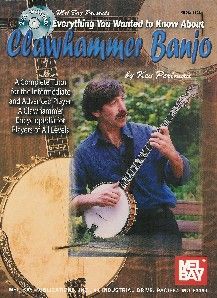

Ken Perlman

(-> FW#23)

is an expert in playing the clawhammer banjo and a pioneer of the melodic style,

i.e. skillfully adapting Celtic tunes to five-string banjo.

Since the 1970s he has been active as a teacher and his "Melodic Clawhammer" column

has run in the "Banjo Newsletter" since 1982. Eventually, everything has been -

updated and revised - put together into a single volume. Beginning at the

intermediate level, so it is a follow-up of his clawhammer tutor,

this melodic clawhammer bible features

almost anything you can dream of -

general issues, the instrument itself,

technique, history and lore,

sharing tips about his playing style,

other kinds of musical genres,

tunings, arranging, backup, etc. -

or is it a nightmare for you?

Since the 1970s he has been active as a teacher and his "Melodic Clawhammer" column

has run in the "Banjo Newsletter" since 1982. Eventually, everything has been -

updated and revised - put together into a single volume. Beginning at the

intermediate level, so it is a follow-up of his clawhammer tutor,

this melodic clawhammer bible features

almost anything you can dream of -

general issues, the instrument itself,

technique, history and lore,

sharing tips about his playing style,

other kinds of musical genres,

tunings, arranging, backup, etc. -

or is it a nightmare for you?

To justify his approach - if you have to justify anything -

Ken digs deep in banjo history:

The Dogon people live near the southern edge of the Sahara desert. [Marc Nerenberg]

was confronted by the local bard carrying a small instrument composed of a round,

skin-covered gourd about six inches in diameter with an attached smoothed stick

about ten inches long. Suspended between the gourd and the stick were two strings.

The bard used a down-picking style instantly identifiable as a relative to clawhammer.

One well-known old-timey tune that was immediately recognizable to the bard as an

African melody was "Reuben's Train."

Beginning in the mid-19th century, the banjo was a prominent feature of traveling

minstrel shows. Banjo pickers of that era played clawhammer style (then called stroke

style) exclusively. Many of the tunes were jigs, reels and hornpipes.

(Many of these were published at the time under other names, almost all of which

began with the word Darkey.)

Interest in playing the 5-string banjo had declined dramatically in much of the

Western world with the onset of the jazz age c.1915: for the most part anyone took

up jazz-friendly 4-string banjos. It was

Pete Seeger's (-> FW#29)

performances and recordings

with the Almanac Singers and the Weavers in the 1940s and 50s that both rekindled

interest in the 5-string banjo, and helped launch the American folk-song revival.

Just about every hybrid one could imagine was practiced somewhere. It was the post

New Lost City Ramblers folk-revival that focused on frailing as the dominant old

time style, and it was the 1970s before the Galax style was adopted by the revival

as the dominant frailing variant. It is also important to remember that the highly

rhythmic Galax style evolved in the post World War II era and was quite different

from the style of frailing practiced in that region by the previous generations

of pickers.

The period in the revival when clawhammer began to eclipse all other old time styles

was roughly the mid-1960s. At the fiddlers' contests you would see lots of

Scruggs-pickers [->

FW#29] and a fair amount of down-pickers. The old time

fingerpickers had either made the transition to bluegrass, or been intimidated

into silence by the high levels of sound-volume and speed that the new style permitted.

And it was to these very contests in the mid 60s that scores of young urban,

college-educated pickers began to flock in search of musical inspiration.

A myth spread with it, namely that this very style had once been widespread throughout

much of the South, and that it was in fact the only truly traditional way to

play old-time banjo.

Most clawhammer pickers play a repertoire consisting primarily of fiddle tunes

and song accompaniments. Ken's collection contains 120 tablatures, the bulk are

americana such as "Arkansas Traveller" (->

FW#26,

FW#27),

"Angeline the Baker" (-> FW#24)

or "Yew Pine(y) Mountains" (-> FW#11),

contra dance tunes like the "Chorus Jig" or "Christmas Day in the Mornin'" (->

FW#27),

and a huge selection of Irish and Scottish tunes. This includes

old friends such as

"Lord MacDonald's Reel" (-> FW#11,

FW#19,

FW23,

FW#23),

James Scott Skinner's "Laird of Drumblair"

(-> FW#24)

or the "Green Meadow Reel" (aka "Over the Moor to Maggie" ->

FW#24,

FW#24),

as well as "Miss Lyall's Reel" (-> FW#28)

or "Neil Gow's Lament for the Death of his Second Wife" (->

FW#22,

FW#22).

But included are also tunes from Quebec, Sweden, France, Hungary, and klez(ham)mer.

Ken points out that playing a 6/8 jig on the five-string banjo is no

un-natural act and confined to the four-string tenor banjo, though

there's no denying that playing jigs in clawhammer style sometimes presents

a challenge for even the dedicated player.

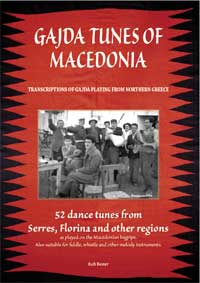

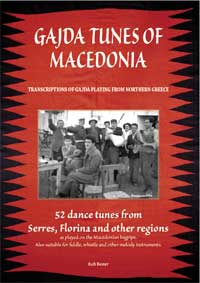

Now we are heading for Macedonia, no, even farther away. Sometimes you have to go all the

way to Australia to get the real thing. As thousands of Greek emigrants alongside other

European cultures did before (-> FW#28).

However it hasn't been emigrants that made field recordings in the 1980s and '90s in

Macedonia and published the transcriptions now as Gajda Tunes of Macedonia,

but Rob Bester and Anne Hildyard of Australian band

Xenos (->

FW#5,

FW#24,

see also CD review in this FW issue). A group the review attests

a surprisingly high level. It's like I'm listening to an authentic Romanian or

Macedonian band. The vocals are just to authentic and the musicians seem to know

what they're doing. The best Balkan CD from outside the Balkan I can think of.

However it hasn't been emigrants that made field recordings in the 1980s and '90s in

Macedonia and published the transcriptions now as Gajda Tunes of Macedonia,

but Rob Bester and Anne Hildyard of Australian band

Xenos (->

FW#5,

FW#24,

see also CD review in this FW issue). A group the review attests

a surprisingly high level. It's like I'm listening to an authentic Romanian or

Macedonian band. The vocals are just to authentic and the musicians seem to know

what they're doing. The best Balkan CD from outside the Balkan I can think of.

The area that bore the name Macedonia during the Ottoman empire was devided

between Serbia, Bulgaria and Greece in 1913. Today the Aegean Macedonia is part

of Greece, Pirin Macedonia is Bulgarian territory, and Vardar Macedonia has become

an independent state. Macedonia's national instrument, better: village instrument,

has been the gajda bagpipe.

The gajda is a bagpipe found in Northern Greece, Bulgaria, Macedonia and in some

parts of Turkey, Romania and Albania. The bag is made from a whole skin, usually

of a goat. The stocks for the pipes are tied into the front leg and head holes.

It usually has a single drone pitched two octaves below the chanter's tonic, uses

single reeds, and is almost fully chromatic over the top half ot its range of an

octave and a tone. The gajda is especially an instrument of shepherds, who have

plenty of time to practice during the summer months up on the mountains with

their herds. It is usually played solo, but can also be accompanied by defi (a

tambourine), daouli (a large drum) or sometimes the laouto (a lute) or lira (a

bowed string instrument). The gajda was once found all over the mainland of

Greece, but in modern bands the clarinet has replaced the gajda.

Proverbs such as without a gajda it's no wedding show the importance of the

instrument and its tradition.

Equally, without efforts like this tunebook there's no chance to keep the gajda

tradition alive. It's certainly filling a gap.

This is the first in a series of books notating dance music of

northern Greece: 52 dance tunes with its often uneven rhythms and including

ornamentation at times, as played on the gajda

with a drone and tonic on A,

but also suitable for fiddle, whistle, etc. which can play the keys of D and G.

In the end, the authors give the advise:

Be careful. Bagpipes are powerful instruments. They were banned by Greek dictator

Metaxas in 1936 as being backward.

So was rembetiko music etc. Be the power of music with you. Thanks a lot and please

give us more - says T:-)M.

Bester, Rob. Gajda Tunes of Macedonia - Transcriptions of Gajda Playing from Northern Greece.

Xenosmusic, 2004, Paperback, 32pp, AUS$25.

Daly, Patricia. Irish Harp and Song Book - Traditional Harp Tutor.

Armagh Harpers, 2000, ISBN 0-9540941-0-7, Paperback, 52pp, UKú10.

Hast, Dorothea E., and Stanley Scott. Music In Ireland - Experiencing Music, Expressing Culture.

Oxford University Press, New York, 2004, ISBN 0-19-514554-2, Hardcover, 153pp, US$17,95 (incl. CD).

Moylan, Terry. The Age of Revolution in the Irish Song Tradition - 1776 to 1815.

Lilliput, Dublin, 2000, ISBN 1-901866-49-1, Paperback, 168pp.

Perlman, Ken. Eyerything You Wanted to Know About Clawhammer Banjo.

Mel Bay, Pacific, MO, 2004, ISBN 0-7866-5890-8, Paperback, 200pp, US$29,95 (incl. 2 CDs).

More Celtic:

FW#19,

FW#20,

FW#24,

FW#26,

FW#27,

FW#28,

FW#29.

German Titles

Back to the content of FolkWorld Articles

Back to FolkWorld issue No. 30

© The Mollis - Editors

of FolkWorld; Published 01/2005

All material published in FolkWorld is © The

Author via FolkWorld. Storage for private use is allowed and welcome. Reviews

and extracts of up to 200 words may be freely quoted and reproduced, if source

and author are acknowledged. For any other reproduction please ask the Editors

for permission. Although any external links from FolkWorld are chosen with greatest

care, FolkWorld and its editors do not take any responsibility for the content

of the linked external websites.

FolkWorld - Home of European Music

Layout & Idea of FolkWorld © The

Mollis - Editors of FolkWorld

"Photographs of musicians adorn the wall; also displayed are poems by Junior

Crehan, the eighty-nine-year-old fiddler who has led these Sunday night sessions for

more than fifty years. When Junior Crehan was born in 1908, Gleesons was a smaller

establishment - a small pub in the farmhouse kitchen. Jimmy and Nell are now the

fourth generation of Gleesons to run the pub. Jimmy recalls that even in his

grandfather's days, there was always music. Every house nearly had some kind of

an instrument, mostly back then a fiddle or a concertina."

"Photographs of musicians adorn the wall; also displayed are poems by Junior

Crehan, the eighty-nine-year-old fiddler who has led these Sunday night sessions for

more than fifty years. When Junior Crehan was born in 1908, Gleesons was a smaller

establishment - a small pub in the farmhouse kitchen. Jimmy and Nell are now the

fourth generation of Gleesons to run the pub. Jimmy recalls that even in his

grandfather's days, there was always music. Every house nearly had some kind of

an instrument, mostly back then a fiddle or a concertina."

This volume obviously focuses on Irish traditional music -

forms of singing, instrumental music, and dance

that are closely interwoven with Ireland's rich cultural history.

Designed for the classroom, but not exclusively limited to it, it is

no tiresome academic lecture. Both authors have a deep affection for the subject,

and both practise the art of Irish music as well.

This volume obviously focuses on Irish traditional music -

forms of singing, instrumental music, and dance

that are closely interwoven with Ireland's rich cultural history.

Designed for the classroom, but not exclusively limited to it, it is

no tiresome academic lecture. Both authors have a deep affection for the subject,

and both practise the art of Irish music as well.

not at least due to the efforts of

not at least due to the efforts of

Since the 1970s he has been active as a teacher and his "Melodic Clawhammer" column

has run in the "Banjo Newsletter" since 1982. Eventually, everything has been -

updated and revised - put together into a single volume. Beginning at the

intermediate level, so it is a follow-up of his clawhammer tutor,

this melodic clawhammer bible features

almost anything you can dream of -

general issues, the instrument itself,

technique, history and lore,

sharing tips about his playing style,

other kinds of musical genres,

tunings, arranging, backup, etc. -

or is it a nightmare for you?

Since the 1970s he has been active as a teacher and his "Melodic Clawhammer" column

has run in the "Banjo Newsletter" since 1982. Eventually, everything has been -

updated and revised - put together into a single volume. Beginning at the

intermediate level, so it is a follow-up of his clawhammer tutor,

this melodic clawhammer bible features

almost anything you can dream of -

general issues, the instrument itself,

technique, history and lore,

sharing tips about his playing style,

other kinds of musical genres,

tunings, arranging, backup, etc. -

or is it a nightmare for you?

However it hasn't been emigrants that made field recordings in the 1980s and '90s in

Macedonia and published the transcriptions now as Gajda Tunes of Macedonia,

but Rob Bester and Anne Hildyard of Australian band

However it hasn't been emigrants that made field recordings in the 1980s and '90s in

Macedonia and published the transcriptions now as Gajda Tunes of Macedonia,

but Rob Bester and Anne Hildyard of Australian band