FolkWorld article by Colin Jones:

"Tibet, Tibet"

Interview with Yungchen Lhamo @ WOMAD 2000

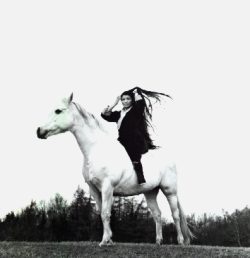

There are probably six or seven hundred people in the Siam Tent at WOMAD 2000. The vast space might intimidate an ordinary performer, but the tiny woman on stage is certainly not that. Her powerful voice soars around the tent, conveying emotion and passion despite the language barrier created by the fact that she sings in Tibetan. This is Yungchen Lhamo, whose first Real World album "Tibet, Tibet" created a stir amongst the World Music community and unusually for an acapella album stayed in the World Music Chart for some months. At the same time she has gravitated in to becoming a spokesperson for her race and what seems to be the perpetual quest to get the powers that be in the west to pressure China to leave Tibet and stop deliberately destroying what little now remains of its centuries old culture.

There are probably six or seven hundred people in the Siam Tent at WOMAD 2000. The vast space might intimidate an ordinary performer, but the tiny woman on stage is certainly not that. Her powerful voice soars around the tent, conveying emotion and passion despite the language barrier created by the fact that she sings in Tibetan. This is Yungchen Lhamo, whose first Real World album "Tibet, Tibet" created a stir amongst the World Music community and unusually for an acapella album stayed in the World Music Chart for some months. At the same time she has gravitated in to becoming a spokesperson for her race and what seems to be the perpetual quest to get the powers that be in the west to pressure China to leave Tibet and stop deliberately destroying what little now remains of its centuries old culture.

Yungchen was born into the Chinese occupation, and like many of her generation has to rely on the stories of her parents and grandparents to get a picture of what life in Tibet was like before the occupation. What is not widely known about the Chinese occupation is the way they deliberately split family units up to lessen any chance of community spirit, and that they also punish the parents for real or imagined transgressions of their children, usually by enforced labour. Yungchen was brought up around her grandmother, as her parents were in enforced labour some distance away and were only allowed to see her about every three years or so. The first songs Yungchen heard were from her grandmother, but they had to be learned and sung in secret because if a Chinese official heard Tibetans singing anything other than praise songs to the glorious cultural revolution it was an offence punishable by banishment, labour camp or imprisonment (and often, torture to remove the 'impure thoughts'). From the age of six Yungchen remembers her grandmother encouraging her to learn and remember more and more of the traditional songs of Tibet. Overt resistance to the Chinese occupation is pointless and is stamped on swiftly and brutally by the army of occupation, but there are many ways of trying to maintain the vestige of Tibetan culture alive behind the mask of subservience that has to be worn in public. Yungchen remembers saying to her mother "What use are songs? What we need is to remove the Chinese army. How will my songs help to do that?" Her mother replied "You have the gift of a wonderful voice, and wherever you go people will listen to your singing. Sing to them of the beauty of your land and people. Tell them about our culture. This will be your weapon. We can all fight and win if we use our best weapons."

It was her grandmother who also encouraged the teenage Yungchen to take the perilous crossing over the border to Dharamsala in India and freedom. Yungchen admits that she was torn about leaving. "There was part of me that was involved in the struggle, that wanted to stay and be with those of my people who found it impossible to leave. Though I did not know my parents very well because we had been kept apart, I had spent a lot of my growing up with my grandmother, and it was difficult to leave her. However, my grandmother was a devout Buddhist, and I had been brought up in the faith too. What sealed my decision to go was the presence of His Holiness the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala. To be in the presence of His Holiness is the ultimate experience for all Tibetans, and it was an experience I knew I could not get if I stayed, so along with about sixty others I made my way across to his palace at Dharamsala." Anyone who thinks this is some Saturday afternoon stroll should read some of the many accounts of this crossing, including that of His Holiness, detailed in his autobiography "Freedom In Exile". It is possibly one of the most arduous journeys in the world, yet it is a road trodden by many thousands of Tibetans each year in search of their spiritual leader and their own 'Freedom In Exile'.

It was her grandmother who also encouraged the teenage Yungchen to take the perilous crossing over the border to Dharamsala in India and freedom. Yungchen admits that she was torn about leaving. "There was part of me that was involved in the struggle, that wanted to stay and be with those of my people who found it impossible to leave. Though I did not know my parents very well because we had been kept apart, I had spent a lot of my growing up with my grandmother, and it was difficult to leave her. However, my grandmother was a devout Buddhist, and I had been brought up in the faith too. What sealed my decision to go was the presence of His Holiness the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala. To be in the presence of His Holiness is the ultimate experience for all Tibetans, and it was an experience I knew I could not get if I stayed, so along with about sixty others I made my way across to his palace at Dharamsala." Anyone who thinks this is some Saturday afternoon stroll should read some of the many accounts of this crossing, including that of His Holiness, detailed in his autobiography "Freedom In Exile". It is possibly one of the most arduous journeys in the world, yet it is a road trodden by many thousands of Tibetans each year in search of their spiritual leader and their own 'Freedom In Exile'.

Yungchen spent the next four years working around the many Tibetan communities in North India, building a reputation as a singer and learning more of the traditional songs of her homeland. She also achieved the objective of meeting with His Holiness too, which memory even now makes her features glow and brings a warm smile to her face. After this time she was encouraged to move out further into the world, and approached several embassies in India for permission to settle. She was given permission to move to Australia, and moved there in 1993, shortly afterwards meeting and marrying the man who was soon also to become her manager. She released an album 'Tibetan Prayer' which won Australia's top music award, an ARIA (Australian Recording Industry Award), and established herself as a top performer there. All this, don't forget, from a woman forced from her homeland as a teenager and who had travelled alone ever since. Musically the rest of her story is simple - 'Tibetan Prayer' was brought to the attention of Peter Gabriel and the Real World crew, which brought her an invitation to come to the UK and record. The resultant album, "Tibet, Tibet" was an outstanding success and the follow up "Coming Home" has produced unanimous acclaim from the critics and enough sales to justify another album, to be recorded in New York and for which Yungchen is currently accumulating material. Whether the new album will be unaccompanied, which is how she usually performs and how her first two albums were recorded, or with musicians like the Hector Zazou produced "Coming Home", is yet to be decided. "When we decide on the material, it will be obvious if the song should be accompanied or not. At this stage, I'm open to either approach. Although I'm used to singing unaccompanied, which is our tradition, it was fascinating to hear the difference to the songs with accompaniment. Perhaps there will be a mixture, who can tell?"

As mentioned at the beginning, Yungchen has also become, as more famous Tibetans almost have to, a spokesperson for her race in their struggle against the Chinese occupation. Like His Holiness, she is both proud and humble about her heritage. "Make no mistake, life in Tibet before the occupation was hard. Many here in the West have the vision of Tibet as some kind of spiritual wonderland, full of people in yellow robes and endless wisdom. In fact it's a hard, unforgiving place in most part without the benefits of the technology that you take for granted here. In return, we do have still a wonderful sense of tradition, of our place in nature, perhaps because we find ourselves closer to it than your society is. The argument the Chinese have consistently used is that we Tibetans are a backward nation, without education and culture. When I sing I ask the world 'Could a people without education, without culture, produce such songs?' There is no doubt that there is potential for much improvement in the everyday lives of our people, but not this way, not by force."

As mentioned at the beginning, Yungchen has also become, as more famous Tibetans almost have to, a spokesperson for her race in their struggle against the Chinese occupation. Like His Holiness, she is both proud and humble about her heritage. "Make no mistake, life in Tibet before the occupation was hard. Many here in the West have the vision of Tibet as some kind of spiritual wonderland, full of people in yellow robes and endless wisdom. In fact it's a hard, unforgiving place in most part without the benefits of the technology that you take for granted here. In return, we do have still a wonderful sense of tradition, of our place in nature, perhaps because we find ourselves closer to it than your society is. The argument the Chinese have consistently used is that we Tibetans are a backward nation, without education and culture. When I sing I ask the world 'Could a people without education, without culture, produce such songs?' There is no doubt that there is potential for much improvement in the everyday lives of our people, but not this way, not by force."

Like many Tibetans in exile she seems almost serene in her identity, and shows no sign of anger or resentment against her country's oppressors. She is quick to point out that this does not mean that such sentiments are not felt, however. "What the Chinese have done and are still doing is totally indefensible. They have killed thousands, destroyed our monasteries, and replaced our own hierarchy of leadership with their own. However, what point is there to create an enemy of China, and of China's allies? We cannot win this fight by force, because our faith teaches us that to do so would be pointless. We create an implacable enemy in China, and we lose our spiritual centre by giving in to our anger. This is not our way, the Buddhist way. We must treat the Chinese as our equals and get them to see that we are also their equals if there is to lasting peace in our land. Only when the differences between our two countries are respected as well as the similarities will there be true peace. Make no mistake; we are angry at the treatment being meted out to our fellow countrymen at home. What the Chinese are doing is wiping out centuries of tradition and culture whilst the rest of the world watches. This hurts us all, very deeply. However, to fight is pointless. Then we both lose. What we want, what our religion teaches us, is that unless we can accept our invaders, absorb them, make them see the value in what we have, in what we are, then there will be no peace. Certainly, to return to what was is impossible. However, to sit idly by, as most countries have done, whilst our culture is being systematically wiped out, is also morally indefensible. No nation should be allowed to behave like this to another."

She speaks all this with a passion that is obviously deeply felt. Her live appearances convey similar passion and it this that communicates itself, soul to soul, heart to heart, beyond any language barrier. Yungchen Lhamo seems to have been destined to be more than just a singer, and she accepts her added burdens with the grace and modesty you would expect from a person steeped in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition. However, even as a singer alone she would be worthy of our attention. The records are highly recommended, but if she should pass your way, the opportunity to see her perform live should not be missed.

Photo Credit: All photos are pressphotos: (1) by Michele Turriani, (2, 3) by Andrew Catlin

Back to the content of FolkWorld Articles, Live Reviews & Columns

To the content of FolkWorld online magazine Nr. 16

© The Mollis - Editors of FolkWorld; Published 10/2000

All material published in FolkWorld is © The Author via FolkWorld. Storage for private use is allowed and welcome. Reviews and extracts of up to 200 words may be freely quoted and reproduced, if source and author are acknowledged. For any other reproduction please ask the Editors for permission.

FolkWorld - Home of European Music

Layout & Idea of FolkWorld © The Mollis - Editors of FolkWorld

There are probably six or seven hundred people in the Siam Tent at WOMAD 2000. The vast space might intimidate an ordinary performer, but the tiny woman on stage is certainly not that. Her powerful voice soars around the tent, conveying emotion and passion despite the language barrier created by the fact that she sings in Tibetan. This is Yungchen Lhamo, whose first Real World album "Tibet, Tibet" created a stir amongst the World Music community and unusually for an acapella album stayed in the World Music Chart for some months. At the same time she has gravitated in to becoming a spokesperson for her race and what seems to be the perpetual quest to get the powers that be in the west to pressure China to leave Tibet and stop deliberately destroying what little now remains of its centuries old culture.

There are probably six or seven hundred people in the Siam Tent at WOMAD 2000. The vast space might intimidate an ordinary performer, but the tiny woman on stage is certainly not that. Her powerful voice soars around the tent, conveying emotion and passion despite the language barrier created by the fact that she sings in Tibetan. This is Yungchen Lhamo, whose first Real World album "Tibet, Tibet" created a stir amongst the World Music community and unusually for an acapella album stayed in the World Music Chart for some months. At the same time she has gravitated in to becoming a spokesperson for her race and what seems to be the perpetual quest to get the powers that be in the west to pressure China to leave Tibet and stop deliberately destroying what little now remains of its centuries old culture.

It was her grandmother who also encouraged the teenage Yungchen to take the perilous crossing over the border to Dharamsala in India and freedom. Yungchen admits that she was torn about leaving. "There was part of me that was involved in the struggle, that wanted to stay and be with those of my people who found it impossible to leave. Though I did not know my parents very well because we had been kept apart, I had spent a lot of my growing up with my grandmother, and it was difficult to leave her. However, my grandmother was a devout Buddhist, and I had been brought up in the faith too. What sealed my decision to go was the presence of His Holiness the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala. To be in the presence of His Holiness is the ultimate experience for all Tibetans, and it was an experience I knew I could not get if I stayed, so along with about sixty others I made my way across to his palace at Dharamsala." Anyone who thinks this is some Saturday afternoon stroll should read some of the many accounts of this crossing, including that of His Holiness, detailed in his autobiography "Freedom In Exile". It is possibly one of the most arduous journeys in the world, yet it is a road trodden by many thousands of Tibetans each year in search of their spiritual leader and their own 'Freedom In Exile'.

It was her grandmother who also encouraged the teenage Yungchen to take the perilous crossing over the border to Dharamsala in India and freedom. Yungchen admits that she was torn about leaving. "There was part of me that was involved in the struggle, that wanted to stay and be with those of my people who found it impossible to leave. Though I did not know my parents very well because we had been kept apart, I had spent a lot of my growing up with my grandmother, and it was difficult to leave her. However, my grandmother was a devout Buddhist, and I had been brought up in the faith too. What sealed my decision to go was the presence of His Holiness the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala. To be in the presence of His Holiness is the ultimate experience for all Tibetans, and it was an experience I knew I could not get if I stayed, so along with about sixty others I made my way across to his palace at Dharamsala." Anyone who thinks this is some Saturday afternoon stroll should read some of the many accounts of this crossing, including that of His Holiness, detailed in his autobiography "Freedom In Exile". It is possibly one of the most arduous journeys in the world, yet it is a road trodden by many thousands of Tibetans each year in search of their spiritual leader and their own 'Freedom In Exile'. As mentioned at the beginning, Yungchen has also become, as more famous Tibetans almost have to, a spokesperson for her race in their struggle against the Chinese occupation. Like His Holiness, she is both proud and humble about her heritage. "Make no mistake, life in Tibet before the occupation was hard. Many here in the West have the vision of Tibet as some kind of spiritual wonderland, full of people in yellow robes and endless wisdom. In fact it's a hard, unforgiving place in most part without the benefits of the technology that you take for granted here. In return, we do have still a wonderful sense of tradition, of our place in nature, perhaps because we find ourselves closer to it than your society is. The argument the Chinese have consistently used is that we Tibetans are a backward nation, without education and culture. When I sing I ask the world 'Could a people without education, without culture, produce such songs?' There is no doubt that there is potential for much improvement in the everyday lives of our people, but not this way, not by force."

As mentioned at the beginning, Yungchen has also become, as more famous Tibetans almost have to, a spokesperson for her race in their struggle against the Chinese occupation. Like His Holiness, she is both proud and humble about her heritage. "Make no mistake, life in Tibet before the occupation was hard. Many here in the West have the vision of Tibet as some kind of spiritual wonderland, full of people in yellow robes and endless wisdom. In fact it's a hard, unforgiving place in most part without the benefits of the technology that you take for granted here. In return, we do have still a wonderful sense of tradition, of our place in nature, perhaps because we find ourselves closer to it than your society is. The argument the Chinese have consistently used is that we Tibetans are a backward nation, without education and culture. When I sing I ask the world 'Could a people without education, without culture, produce such songs?' There is no doubt that there is potential for much improvement in the everyday lives of our people, but not this way, not by force."